The previous unit dealt with telepresence and virtual worlds. As we start to design and implement multiplayer *mechanics* it’s time to talk about online games in a narrower sense.

You can find plenty of complete histories of online games on the internet, the examples here are intended to introduce specific concepts.

Maze War (1973)

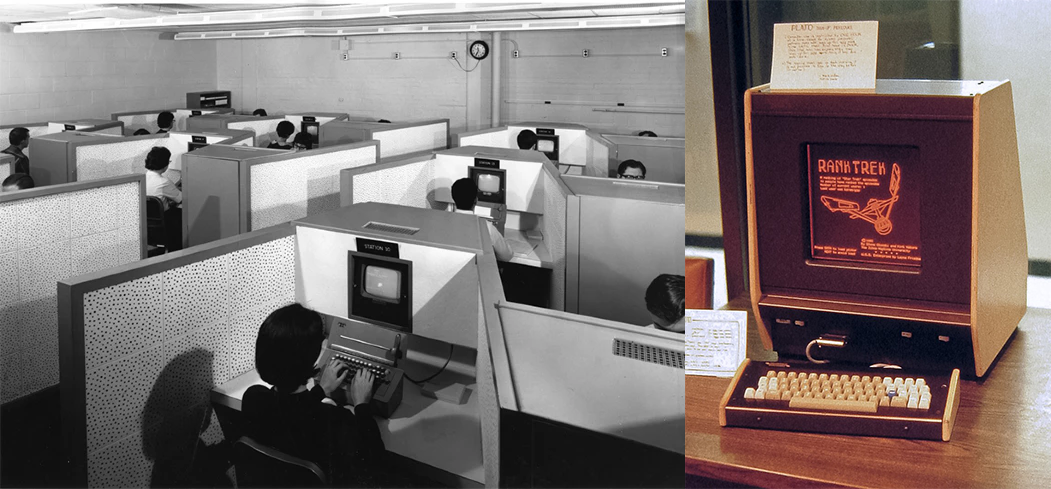

The first computers were not “personal”, they were terminals connected to mainframes and existed only in university labs.

This is game industry prehistory, as a time reference consider that Pong came out in 1972-3 as a cabinet, and the first Atari cartridge console came out in 1977.

Maze War was the first FPS, and it was an online player-vs-player multiplayer. Online at that point meant playable on ARPANET between multiple universities.

It introduced a lot design solutions we take for granted now.

PLATO

PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations), was the first computer-assisted learning system in wide use. It was a network of computers (mainframes, terminals, phone, and custom programming tools) established by the University of Illinois in 1960.

By 1972, it offered vector graphics (in monochrome orange), touch-screen interface (!) and connection to ARPANET, a pre-Internet network among US universities, research centers and defense agencies.

The first online multiplayer games were made on PLATO by students.

Some notable examples:

(the video is from an emulator)

Star Trek inspired, galaxy conquer game with strategic and tactical elements.

Up to 30 players could be in the game at once, with no more than 15 players on a team. Each player is given a starship to pilot. Players dogfight each other, destroy enemy armies by bombing them, beam up friendly armies to transport them, and beam down armies to take over planets.

Different “races” with different stats.

Commands involving directions to change course and fire weapons are entered as degree headings.

It was technically an action game but the limits of the system made it more tactically deep since the update rates were dependent on the screen refresh. You can read a gameplay breakdown here

Inspired by the tabletop RPG, involved character creation with stats, non-linear progression, quests, levels, and “bosses”.

Around 15 players would go on adventure. The party leader would control the movement of the entire group, but each player would control its character during combat.

Moria was a dungeon crawler, role-playing video developed around 1975.

It allowed parties of up to ten players to travel as a group and message each other, dynamically generating dungeons, and featuring a first-person perspective (not real time 3D, that will be introduced by Battlezone).

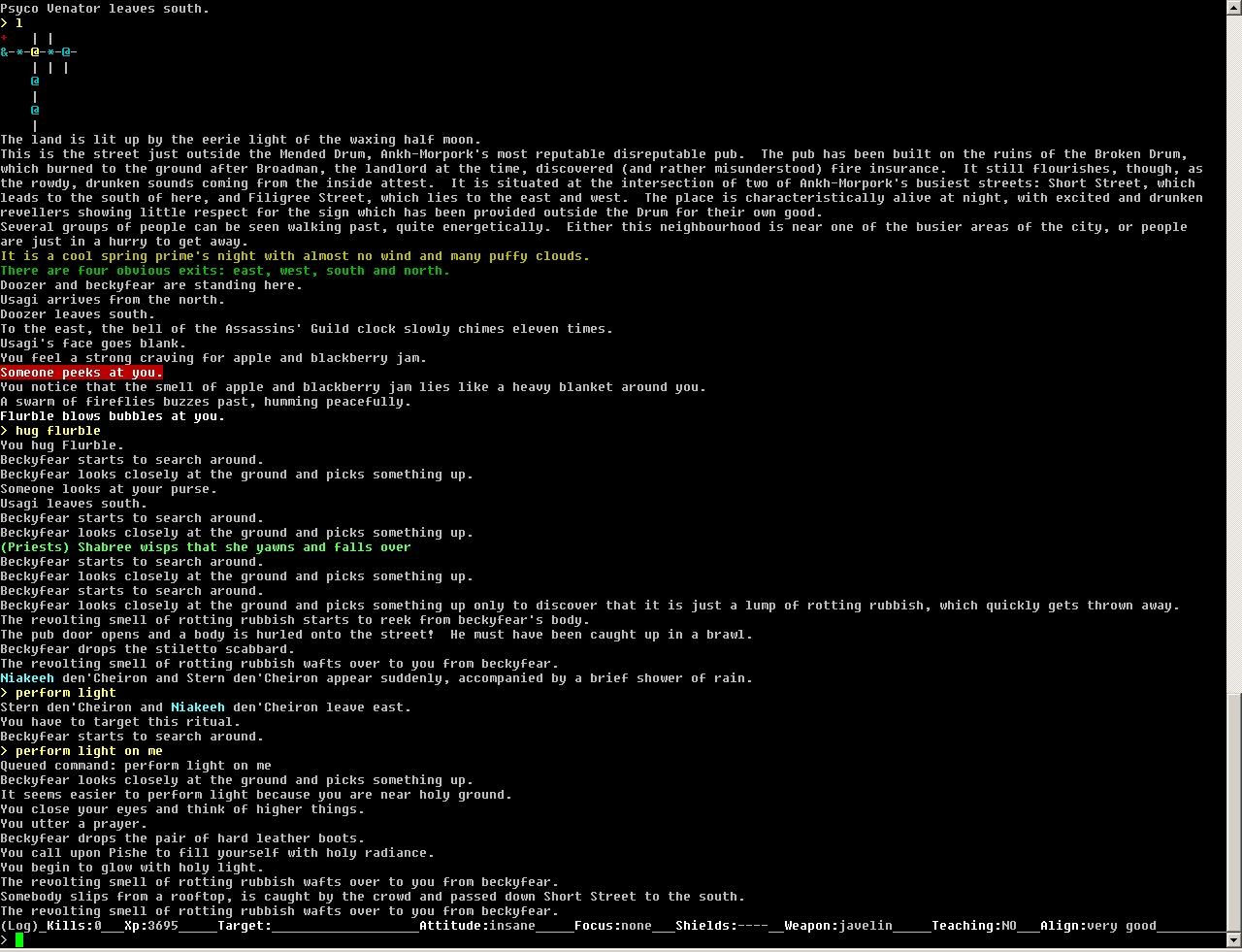

MUDs – Multi User Dungeons (1978-)

MUDs essentially added multiplayer features to text adventures like Zork starting from 1978 (still ARPANET and University networks).

Let’s visit Discworld MUD (1992)

Here’s a map if you get lost:

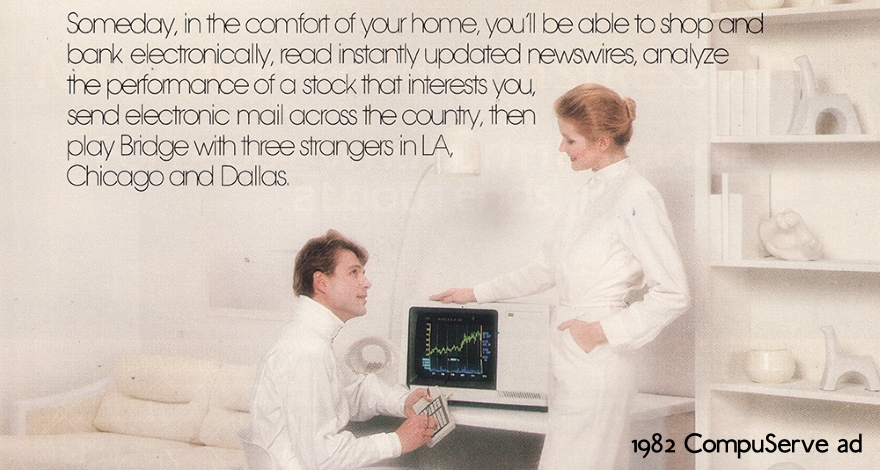

In the mid 80 MUDs were packages in the offers of early online service providers along with email, online newspapers, chat rooms and BBS (forums). Accessed through phone lines and paid by the minute.

MUD had grinding and leveling but thanks to the flexibility of text they had a strong element of exploration and world building.

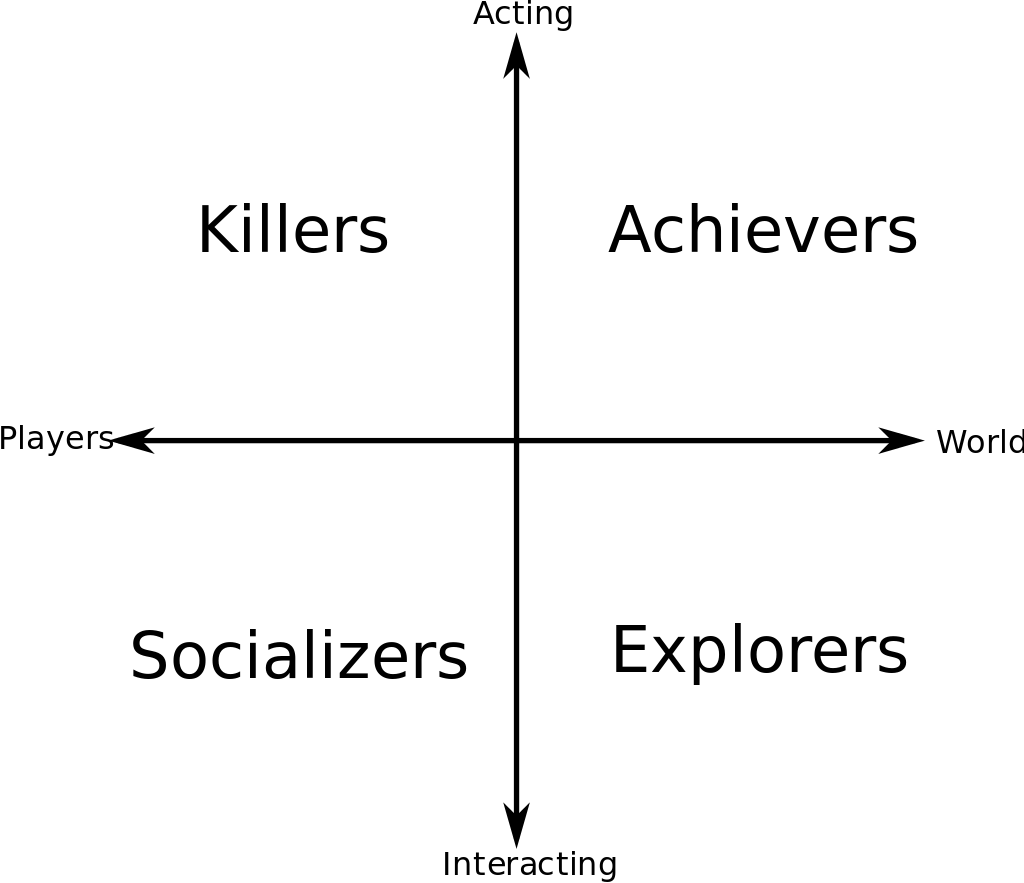

Richard Bartle co-creator of the first MUD became a theorist of online world and created an influential taxonomy of players, also applicable to single player games.

You can try this vintage test to find out who you are (in 1996)

What are some actions or verbs associated to these types of players?

What are some design patterns and features used to attract a certain type of player?

MUDs may be have been a niche back then but they were a foundational experience for the designers of the following generation of online games.

Even if this “history” is western-centered it’s worth noting that MUDs were popular in South Korea as well and the played a similar foundational role.

Doom (1993)

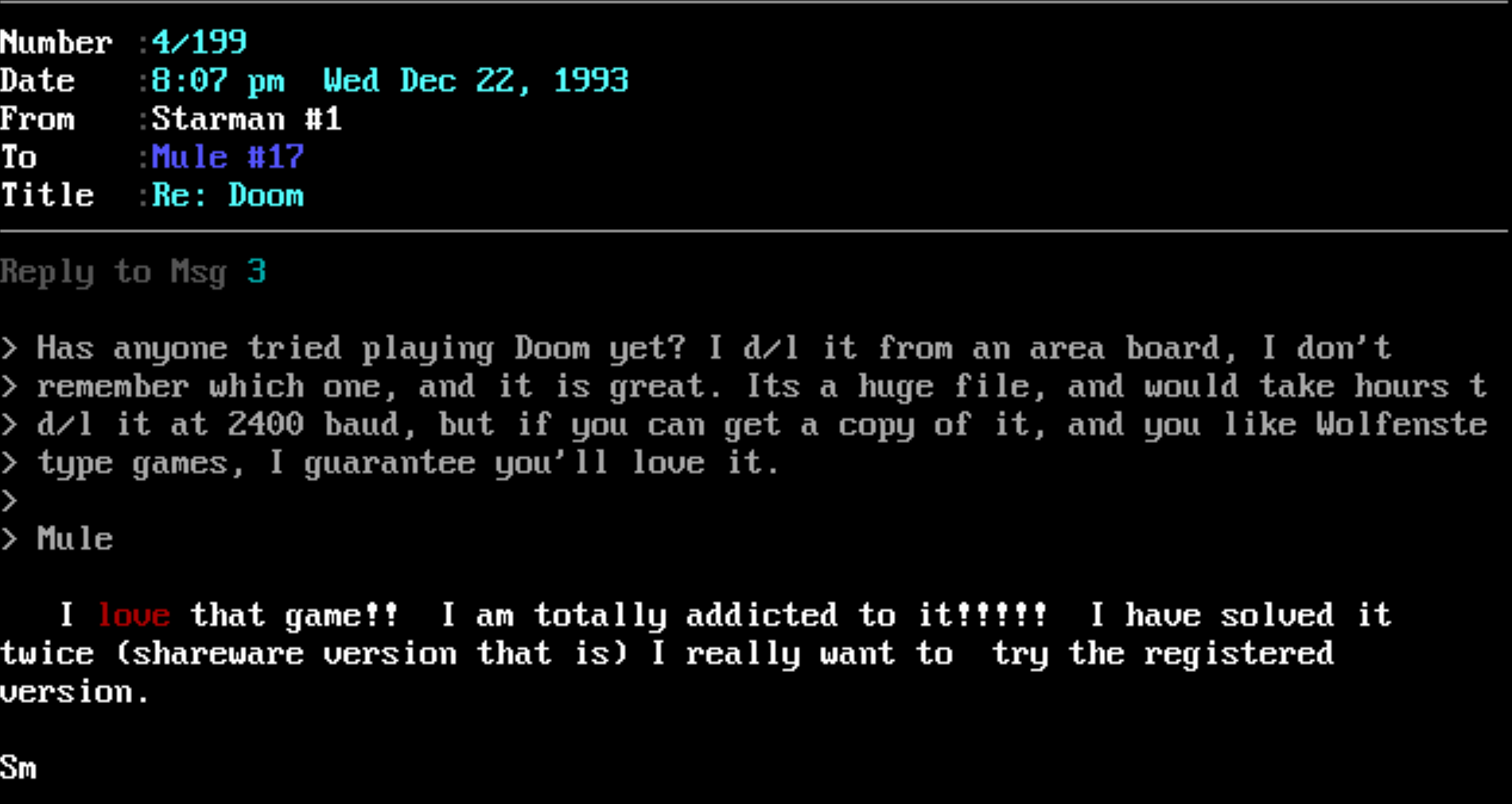

The extremely popular and influential Doom could be played via LAN (local network) and online.

Doom II improved the multiplayer capabilities and allowed for cooperative and deathmatch game modes.

Humans > AIs

“Sure, it was fun to shoot monsters, but ultimately these were soulless creatures controlled by a computer. Now gamers could play against spontaneous human beings—opponents who could think and strategize and scream. We can kill each other!”

– John Romero

Not-so-obvious intuition back then: player-vs-player allows for a higher level kind of play (see esports now), and higher emotional investment since you are “killing” your friends (or strangers).

Doom started as an independent, low budget, project and became “virally” successful as shareware (freely distributed demo) among BBS (pre-web internet forums that allowed file sharing).

Playbor

Doom also leveraged the power of online communities by allowing level creation and mods (modifications).

Id software released the source code of the game allowing for further community development.

The practice of opening up parts of the game to audience modification became quite common in the industry at the time. Half life had software development kit that allowed the creation of entirely new games such as:

Counter Strike (1999)

One of the most popular multiplayer fps of all time started as a mod of Half-Life. The creator was quickly hired by Valve.

Counter Strike introduced a few asymmetrical team-based game modes, planting bombs etc.

Perhaps more crucially, it came out right before 9-11 and the War On Terrorism.

esports

Counter Strike:Global Offensive dominated the early esports scene, from 2001-07 or so and it’s still popular today.

“Professional” gaming tournaments have been around for a long time, but esports are a more recent phenomenon. What makes a game an esport?

What do you think made Counter Strike a popular esport?

CS:GO had a tournament-friendly strategic element. What happens in one round will carry over the next. Players must purchase the equipment they wish to use at the beginning of the round.

If you survive the previous round, you get to keep your gear.

It also had couple of popular maps that became standard playing fields, like Dust II.

Every high level player (and viewer) knows every single nook of the map, so the game is about making the right tactical decisions among many known options, as much as it about shooting fast and precisely.

Cheat-detection

As the competitive CS scene became more high stakes Valve had to come up with sophisticated anti-cheat systems that detected hacked clients and banned users (with an unpredictable delay).

Persistence

Doom, CS:GO, Starcraft, MOBAs, and many competitive pvp games don’t have persistent worlds.

They involve only a few players in sessions limited in time.

The scenarios reset at every game, even if sometimes the player stats and virtual items persist.

Persistence is pretty what differentiates MMORPG-type of games and virtual worlds.

Ultima Online (1997)

Like Doom and later WoW, Ultima Online was built upon a popular franchise of single player games.

Ultima games were rich open world RPGs with a complex crafting mechanics.

Game Economies

Ultima was the first massively persistent game with enough players to for complex in-game economies to emerge (here I don’t mean players making money programming virtual items but roleplaying as artisans, fishermen, and so on).

The creator Richard Garriot estimated that about half of the players were not adventurers but just ordinary people who never left their villages.

Still, some of the peaceful player yearned for online games with more satisfying and dignified mundane tasks. Check out this post from 2000 I want to bake bread. [a letter to game developers]

The suggestions are very specific and still valid today for non combat based design:

“I’m an under served part of the Massively Multi-player Online Game (MMOG) player-base. I’m not a large part, and you’d be a fool to base your whole game around me. But I think I’d make a welcome addition to your bottom line.”

“I’m also a fairly untapped market. It’s been a few years since a game has come out that even attempted to attract me. ”

“You see, it’s not just bread I want to bake. I also want to bake armor and dresses, phasers and chairs, scrolls and steam engines, swords and plow-shears, blasters and potion. I want to bake bread and anything else that you think is relevant for me to bake in your game.”

“The things I make have to be desirable to at least some of the other players of your game”

“It should be possible for me to reach the same status –fame, loot, rank, level, gold…(whatever you use)– as other segments of your player-base (Monster Hunters, Explorers, Player Killers, Role Players…).”

“As much as I like the idea of the items I make having a permanent place in your world, it’s more important to me in the long run that your economy works. With that in mind, don’t forget to include mechanisms for the items I create to: age / break / be consumed / need repairs / need recharging / decay / wear out / or whatever seems appropriate in your game.”

Everquest (1999)

First successful 3D MMORPG and template for many others. It dominated the genre until WoW.

Group raids, different races/class combinations corresponding to tactical roles, generally speaking:

tank – drawing enemies’ attacks toward themselves and absorbing damage

healer – keeping allies alive by healing their wounds and protecting them from harm

damage dealer – those with the highest Damage Per Second

You seen from the video many UX solutions later adopted by WoW.

Expertise

MMORPG are examples of maximalist design. They are full of collectible, quests, creatures, abilities, expansive lore: the more the better. Part of the fun is to learn about all the stuff.

Much of the social element is learning from more experienced players and teaching to less experienced ones (newbies, or noobs).

MMORPG are designed to exceed the comprehension of a single player.

Social hierarchies are formalized in “levels” but also in this kind of expertise.

World of Warcraft (2004)

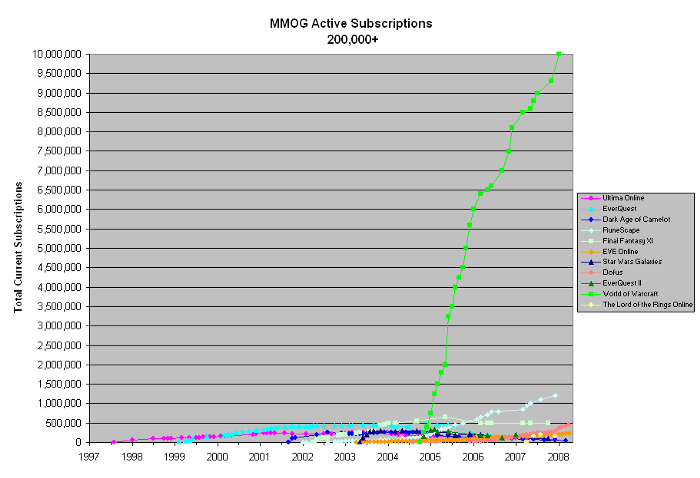

Popularity

Let’s have this part of the class in WoW, but first look this graph.

~10M is the player count at its peak, users had to buy the game and pay a monthly subscription at that point.

If there are current and former WoW players among you, what do you think made this game so successful and what are the aspects you liked the most?

According to early adopter WoW was much more polished, more visually appealing and less buggy than its competitors.

It also had clear progression paths that made it more accessible to new users.

WoW had various system to avoid player vs player (pvp) combat, and being pwned by more advanced users (unless you wanted to).

It was built on a successful franchise and had good writing and deep lore.

It was also designed to be compelling as single player game.

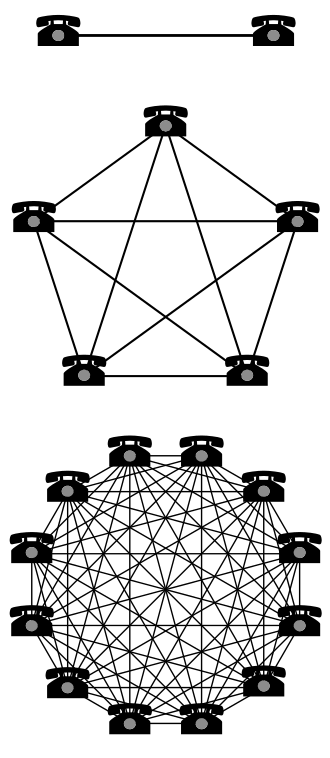

Network effect

WoW’s quick growth is similar to that of some social networks at the time. When they pick up they really do. This is sometimes explained with the Reed’s Law (derived from the Meltcafe’s Law) that the value, or the utility, of a social network, scales exponentially with the size of the network.

You can form exponentially more affinity groups, maintain more relationships. You are exponentially more entangled as the network grows.

Leveling

In roleplay oriented virtual world avatars are about self-expression and identity performance.

In a combat-oriented games they are also an asset, something you put time and labor into.

The more you play, the more agency and power you have, the harder it is to switch to another game and start all over.

Gold farming

Have you ever heard about it? Is it still a thing?

Gold farming is the practice of playing a massively multiplayer online game (MMO) to acquire in-game currency later selling it for real-world money.

Usually it involves grinding or adopting repetitive, low-risk, play styles.

It’s considered a form of cheating by many players and became a cottage industry, especially in China, around 2006.

What makes gold farming viable? Why is a thing?

Unequal distribution of wealth globally. Rich players with little time, “poor’ players with a lot of time.

The predominance of Chinese gold farmers created racial tensions withing MMORPG affecting also ordinary (leasure) Asian players.

During an economic crisis a lot of Venezuelans started gold farming in WoW creating in-game inflation.

Addiction

WoW is not a “casual” game, it requires and rewards commitment.

Its massive growth and the heavy usage of many players spawned a debate on video game addiction that is still ongoing.

While the medical pathology status of video game addiction requires further study, there has been a criticism (and self-criticism among game designers) of addicting patterns: is it ethical to design a game for addiction, that is to maximize the time a player spends with it?

Where is the line between between engaging and exploiting the players’ weaknesses?

What are some “dark” patterns in games that could be considered addictive?

FOMO, the game is always on, your friends or enemies may be having fun right now.

Due to the social nature, even when you are playing an MMO can’t be paused.

Even in single player or match-based games you can find design pattern that minimize downtime and encourage the “one last game/ one last quest” behavior.

Infinite progression, there’s always something better and cooler to acquire right around the corner, keeping up with the virtual Joneses. When you reach the ceiling there are new expansions.

Scheduled game events, such as weekly raids, or monsters or materials that respawn at given intervals, can be considered addictive because they force the player to schedule or neglect their life committments around the game (see Farmville and play-by-appointment below).

A game can be unclear or misleading about the time commitment required for a task. If players feel like they “wasted their time” it may be a sign of unethical game design.

Perception of value and loss: you pre-paid for a game or a subscription, and you don’t unlock the full content you perceive it as a loss.

By the way, after this session you are going to uninstall WoW with the screen sharing on.

In-game protests and avatar rights

Real life politics often enters online games, ie Second Life protests or artistic interventions – but there is also internal game politics, typically conflicts between players and designers.

MMORPG are constantly tweaked to ensure balance in a constantly expanding gameplay.

When it comes to nerfing and buffing common powers or classes conflicts can emerge, as the (privileged) subject may feel treated unfair.

WoW players staged several “class” protests such as the Million Gnome March which, like a real life demonstration, actually impacted the game server and was followed by a brutal repression from Blizzard.

Developer-player conflicts prompted many to wonder about the rights of the players. Are players’ just Terms-of-service-bound customers in a world that so meaningful for them? Who owns the avatar? What is sovereignty in a territory entirely controlled by a corporation? Does freedom of speech apply in online games?

These questions foreshadowed current issues with data ownership in social media.

A Declaration of the Rights of Avatars by Raph Koster (2000)

Koster would later become a designer of Star Wars: Galaxies, a game that coincidentally went through some major conflicts between players, developers, and publishers.

Racial representation and cultural borrowings

Problematic gender and race representations are not new to online worlds and come from the long history of high fantasy tropes. However, WoW missed an opportunity to re-imagine fantasy for the 21st century.

Even if the Azeroth is a separate fantasy dimension, certain races are “coded” in that they borrow elements from real world human groups.

When combined with an overarching good-vs-evil narrative, and roleplay, problems may arise. Some examples:

Gnomes, dwarves and humans seem to signify the West, with gnomes and dwarves closely connected to capitalism and technology. The only alliance race with darker skin is the Night Elves, and they are viewed with suspicion by other alliance members.

The visual iconography of the horde races suggests real-world cultures (e.g. totems, tents, face paint), and the horde in general are portrayed as “primitive.”

The trolls speak in recognizably Jamaican accents, and the emotes for the male reinforce highly sexualized stereotypes. They are evil and sadistic.

Their cultural signifiers are a mix of Caribbean, Mesoamerican, African, and Polynesian cultures (AKA The “Savages” of the age of exploration) Zandalari are obviously Incan. Also they practice voodoo.The alliance actually locked the Orcs up in internment camps, a move which she compares to the Indian Removal Act of 1830. She writes, “The Orcs’s bloodthirstiness was subdued during their stay in internment camps, which is a disturbing sort of justification for the imprisonment and enslavement of another race of people.”

Tauren reference the nomadic native american tribes of the middle USA, but only the surface elements and mashing various tribal tradition.

Pandaren, a relatively new race, directly reference Chinese culture, names, fashion and architecture.

Are there any games or pop cultural products that portray fantasy cultures in a respectful or non-jarringly-referential way?

Sources and more articles on the subject:

Beat Those Sleepy Slackers!: Color-Blind Racism in World of Warcraft’s Valley of Trials

Cultural Borrowing in WoW

Our Conversation On Race In ‘World of Warcraft,’ Unabridged

Gender relations

In early 2012 Angela Washko founded “The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft”

Instead of continuing to following the quest structure of the game – killing dragons, getting better equipment, joining more competitive guilds…while performing as “The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft,” Washko facilitates discussions with players inside the game about the ways in which the communities therein addresses women and how players respond to the term “FEMINISM”.

Washko is interested in the impulse of the player-base to create an oppressive, misogynistic space for women within a physical environment that is otherwise accessible and inviting.

I hope to help to create an environment that encourages women gamers to participate. I also present performances and videos to a non-MMO-informed public that is unaware that these communities exist.

In this particular performance, I discussed several male players’ decision to play female toons (avatars) and also got into a discussion with a female player about her belief that if you wear revealing clothing it’s your fault that you get raped (hardcore slut-shaming).

Farmville (2009)

It may be semi-forgotten now but at its peak, in March 2010, this ugly farm sim had 83.76 million monthly active users (34M daily or more than 3 times WoW).

Farmville was basically a clone of other games like Happy Farm (popular in China and Taiwan), and Farm Town but it became hugely popular thanks to the integration with Facebook.

Social network games had a quick boom and a bust cycle as players moved to f2p games on mobile and Facebook prevented apps from spamming friends, limiting their viral diffusion.

Asynchronous play

Farmville’s multiplayer element was rather light and asynchronous.

It allowed players to visit their friend’s farms and help out, whether or not that friend is online.

The social mechanics were basically oriented toward user acquisition:

every time you perform an action, a message pops up and asks you if you would like to share with your friends.

Free to play

Social Network Games pioneered the Free to Play business model, immediately followed by mobile games and eventually by AAA games.

Do you play free to play games? What do you spend money on?

Free to Play games are free but they rely on in-game purchases.

Sometimes these digital commodities are cosmetic, for self-expression and prestige like in Habbo.

Sometimes they buy expansions, or the full version of a game, or remove ads.

Sometimes the transactions are stimulated with less ethical design patterns identical to those used by the gambling industry.

F2P Games companies hired data analysts and cognitive psychologist en-masse and adopted flexible designs. Every player action was tracked and the gameplay tweaked to optimize engagement and sales.

Ken Rudin of Zynga infamously stated that Zynga is “an analytics company masquerading as a games company”.

Some dark patters used by Social Network Games became common practice in the industry, especially in mobile games.

Pyramid schemes: rewarding players for promoting the game (and instrumentalize friend and relationship)

Impersonation: sending notification to a friends like “Betty sent you a gift” (SimCity Social) communicating actions they never performed or that were never meant to be shared. See also LinkedIn.

Pay to skip: making grinding extremely tedious and then offering a paid shortcut.

Pay to win: selling items that offer an advantage in competitive games (the most controversial pattern).

Loot Boxes: paid items with random rewards aka slot machines aka gambling.

Dark Patterns in the design of games

Loot Boxes Are Designed to Exploit us

Whales

It’s important to note that such business model, like gambling, often relies on a small percentage (sometimes less than 1%) of big spenders aka whales. Many f2p games are specifically designed to entrap these users.

More often than not, whales are not rich players, but just people vulnerable to a gambling habit.

Chasing the Whale: Examining the ethics of free-to-play games

Sources and more in-depth articles

ROBLOX is a MUD: The history of MUDs, virtual worlds & MMORPGs

Out of the MUD: The Origins of the MMORPG – RPG-oriented history of online games (video)