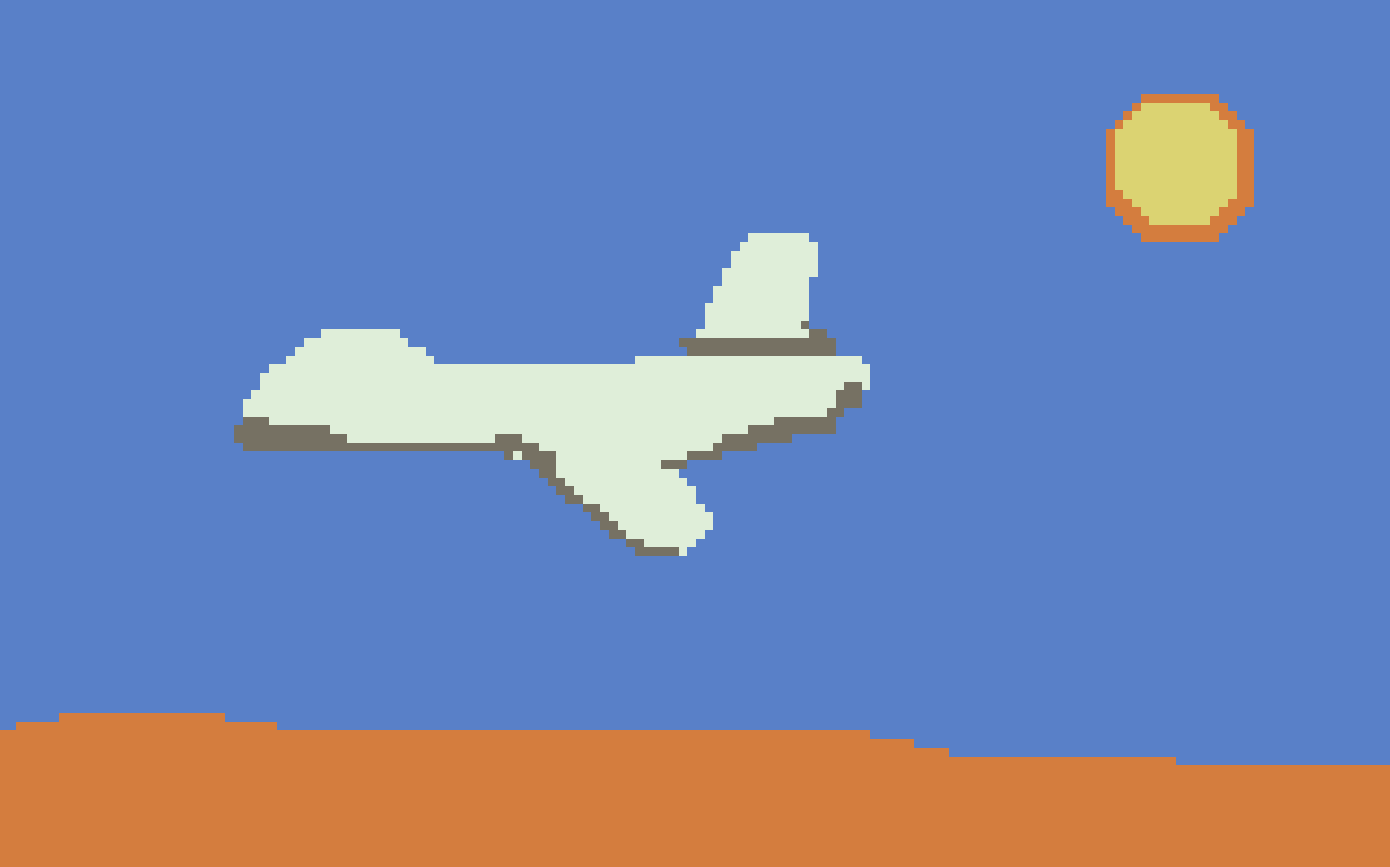

The first thing anyone with any knowledge of video games will notice about playing Number None, Inc’s Braid is that the mechanics of the game are a reference to Super Mario Brothers, from the simple fact of being a side-scrolling platformer, to the goomba-like enemies which one can only defeat by jumping on them. But the reference to Super Mario is not just a mechanical one; it turns out to be an important tool through which narrative meaning is conveyed. The first on-the-nose hint of this comes when player reaches the end of stage one and encounters the familiar scene: a friendly character emerges to deliver that classic bad news that the princess is in a different castle.

Cutting to the game’s end, it turns out that the player character is a scientist working on the Manhattan project, and the “princess” in the story is actually the player’s goal of completing the atomic bomb. This would be an impactful revelation on its own, but where things get really interesting is in the existence of an alternative ending. In the regular ending, you realize that due to your own warped perspective, the princess you thought you were rescuing has actually been running from your pursuit the entire time, revealing you to be the bad guy. But there’s a second ending, and because it is harder to reach, anyone used to the convention of alternate endings in games is likely to perceive this as the “true” or “best” ending. But in the alternative ending, the moment you reach the princess the bomb detonates. The good ending is also the bad ending.

This method of conveying a moral message by confronting the player with the idea that they were complicit in evil just by playing the game is not uncharted territory. It’s also a tricky device to really make work, since above any challenge to the player’s morality within the game is the fact that the developer built and marketed the game in the first place. What makes the alternate ending in Braid so meaningful however is the fact that the way to reach it—a perfectly timed jump onto a moving set piece—happens so quickly and without precedent that it almost feels like a mistake on the developer’s part. To be attempting this trick in the first place feels like trying to break the game, the aim of which—reaching a platform that seems like the game wasn’t designed for you to reach—is reminiscent of the same trick in Mario which leads to the warp zones.

What’s present in the nuance of this alternate ending is that first you must find out you’re the bad guy, and then you have to still be so determined to reach your original goal, so unfazed by the realization of the full implications of your mission that you’re willing to try to break the game to reach it. By referencing Mario, which itself references a common trope of rescuing a princes, Braid creates an occasion to reflect on a multitude of games the player has played in the past and consider a deeper reality for the characters than what was originally perceived, or even beyond what the developer may have intended. Braid opens the question: what exactly was Mario’s relation to Princess Peach, or Link’s relation to Princess Zelda beneath the surface of what the developers presented?