What is a prototype?

-A game prototype is not a finished product but a dynamic, computational “sketch” of your game, a proof of concept.

-Prototypes are usually developed with the fastest techniques: paper, accessible editors, pre-existing engines, “fast loop” game engines like Unity.

-Because of that, prototypes in the industry are typically thrown away, even if they are successful. The actual development starts from scratch.

-Prototypes use placeholder assets. Concept art can be done separately to set a style and visual/polish goal.

-Most prototype fail: turn out to not be good or feasible ideas or don’t generate the desired dynamics (fun or else). That is not a problem.

Why prototyping?

The reasons for building a prototype are varied. Here are some examples:

> To have a finished game at the end of a fixed time, such as in a game jam

Indie games that started in a jam

The concept can be stated in one sentence: a FPS in which time progresses only when you move.

“We made our prototype at the Global Game Jam, and we also made a video of people playing it,” said Kane. It got a surprising amount of views, so of course, one of the team members quit his job and they went all in on developing the game full-time.

“Demoing was going to be this ongoing process, all throughout development”

Joke tweet from a parody account

Molyjam a Game jam based on the joke account.

Nice story outlining the missteps and lessons from prototype to final game.

Games ideated within company-wide “jams”

Goat Simulator: started as a joke in an internal jam, made $12 million in revenue, created the youtube bait genre.

”

Costume Quest is a result of a series of “Amnesia Fortnights” that Double Fine had used during the period of Brütal Legend‘s development when they were unsure of their publisher. During the Amnesia Fortnights, the team split into four smaller groups and worked on prototypes for potential future games, later presenting these to the rest of the Double Fine team for review.

Student games that became commercial projects

Game Mods as prototypes

> To have the core of a game playable quickly. Especially if it’s a risky and novel idea.

Nintendo ARMS

The prototypes

Zelda Breath of the Wild

The prototype

Braid

(proto starts at 26)

> To select the best idea from a set of alternatives.

Journey

> To test the technical feasibility of an idea: where the idea can be anything from a full game to a graphics technique or AI algorithm.

Such prototypes attempt to respond a well formulated question

Left 4 Dead companion AI

(start at 9min)

Minecraft terrain generator

What is a good prototype?

It depends on the purpose. In general from a good prototype you should be able to tell:

> Can the player make meaningful decisions?

> Is the player getting the feedback they require to make good decisions?

> Are the major risk / reward schedules in place?

> What is the pacing of the experience?

> Is there enough meat here to hang the rest of the game on?

From Common game prototyping pitfalls

How to prototype

Obviously there is no definitive answer. Assuming you already defined the concept or the question that the prototype is supposed to answer, my recommendation is to roughly follow this path (a for programmers and b for artists):

1- Paper prototype in your head as much as you can: make sketches and mockups to visualize your idea. If you are working within a team, use big sheets of paper or dry-erase boards, letting every member clearly see and participate.

2a- Look for a tool or a template that simplifies the non-experimental parts and takes care of the basic infrastructure, especially if it’s a twist on an established genre (e.g. super hot).

2b- Gather concept art and music to create an emotional target.

3a- Implement the controls and create a “toy” around your core mechanic. A toy is not a game, it has no goals, no levels. It’s just a dynamic, interactive system.

3b-Identify an economic workflow for your assets creation. (We’ll talk about economic visual strategies soon).

4a- Implement a goal based on the interaction that feels more fun or interesting. At this point you may even reconsider the original theme. Embrace happy accidents, don’t get too attached to the original pitch.

4b- Identify a key asset that will define the visual style. If working in 2D create a mock screenshot. Work on many assets in parallel: you don’t want to end up with a detailed avatar and an incomplete level.

5a- Add only one secondary mechanic or element at a time. Does it integrate with the previous moving parts adding complexity through emergence? Does it break the original mechanic? Iterate until you are out of time.

5b- Add the music as soon as you can, add visual assets even if they are still temporary. Proceed by incremental refinements. Iterate until you are out of time.

Other general principles, easier said than done:

– Keep in mind this cartoon about the concept of minimum viable product

-Cut all corners, hardcode everything if it’s faster, fake it, don’t worry about messy code or inelegant data structures.

– Agility: make your prototype easy to change and tune. This can be at odds with the point above.

-Before implementing something, ask yourself it’s strictly necessary or if just something you are adding because you’ve seen it in other games

-Identify and avoid time drains. Some non-core aspects can take a long time to implement: GUI, animation, procedural generation, cutscenes, etc.

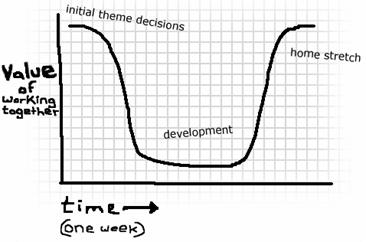

-Multiple programmers and multiple artists can be a problem under severe time constraints. You shouldn’t spend too much time communicating, coordinating and making production schedules.

-Continuous feedback and collaboration may not always be useful when prototyping:

In some context it makes sense to parallelize the prototyping phase, in order to create friendly competition, and try more ideas at the same time, and mitigate the risk of failure.

In some context it makes sense to parallelize the prototyping phase, in order to create friendly competition, and try more ideas at the same time, and mitigate the risk of failure.

*Some points are adapted from the classic: How to Prototype a Game in Under 7 Days