Videogames writing – and dialogue in particular – is often pretty bad compared to other narrative media like cinema, TV, literature, theater, or animation. Here are some common reasons:

- Storytelling is subordinated to the game mechanics. The story has to retroactively justify the player actions (killing, solving puzzles, etc) instead of driving them. For example extreme, generalized violence doesn’t leave room for moral subtlety resulting in ludo-narrative dissonance – a perceives dissonance between the narrative component and the gameplay.

- Writers are brought in at a later stage of the development process and don’t have the chance to shape the narrative and the characters, they are only expected to put words in pre-defined boxes.

- Dialogues serve only an expository function, and characters are there to “serve” the player. This results in an ATM style of dialogue in which the NPCs (Non Playing Characters) are mere repositories of information.

- A long tradition of sloppy translations and localizations of foreign, in particular Japanese games (a problem that seems shared even by Korean hit series Squid Game)

- The narrative structure doesn’t offer opportunities for psychological depth, focusing instead on clearly communicated, binary moral choices like do the “good” thing vs do the “bad” thing.

- Voice acting is disjointed and stilted due to cumbersome motion capture technologies. Actors don’t have a chance to react to each other, workshop their lines, or improvise.

LA Noire was considered groundbreaking in terms of performance capture, it was still pretty awkward and uncanny.

- Natural dialogue patterns like cross-talk, interrupting each other are technically hard to implement with voice acting or text. Flows and rhythms are interrupted by player choices. There is a trade-off between narrative agency and smooth storytelling.

Oxenfree employs a sophisticated real time dialogue system. Unfortunately it’s mostly used in the first 20 minutes.

- Many common narrative devices can’t be used due to a commitment to a continuity of time and space and a single playable character. If you are constantly following a protagonist you can’t leverage an asymmetry of information between characters, which is the basis of a lot of humor, suspense and drama.

(Eg. Oh no! the protagonist doesn’t know the monster is around the corner!)

Disco Elysium deploys literary techniques like flow of consciousness, (semi)omniscient and unreliable narrators through a cast of internal characters/RPG skills.

Dialogue Writing Workshop

In this workshop we’ll try to give our characters unique voices through a variety of screenwriting techniques and exercises.

Keep in mind: writing dialogue requires a lot of practice, a lot of research, and even some innate psychological intuition. This is just a series of bullet points to avoid some common pitfalls and give a minimum amount of depth to your characters.

-

Define the characters

Choose two or three characters from your game to be part of a dialogue. The conversation can be part of the game as it is now or hypothetical, as an exercise in characterization.

For each character write down:

What do they want?

A character should have a goal or need to fulfill, the need should propel the story forward and come in conflict with other characters’ goals. The overarching motivations should be broken down at the level of the individual interaction. What are they trying to get from each other?

Who are they?

Gender, age, race, wealth, nationality, job, education, ideology, unique habits, friends, family, time period…

Not everything will emerge over the course of the game but it will help ground the character in a social and historical context. This basic information should inform names, visual design, affectations, accents.

Astrologaster’s protagonist is inspired by a real historical figure and everything its characters’ do or say is informed by their class and habits and beliefs of Elizabethan England.

What’s their background/backstory?

Again, not everything will surface in your story but having a better understanding of what happened to the character, how they became what they are, will help you conceive more complex and credible characters…

What are their personality traits?

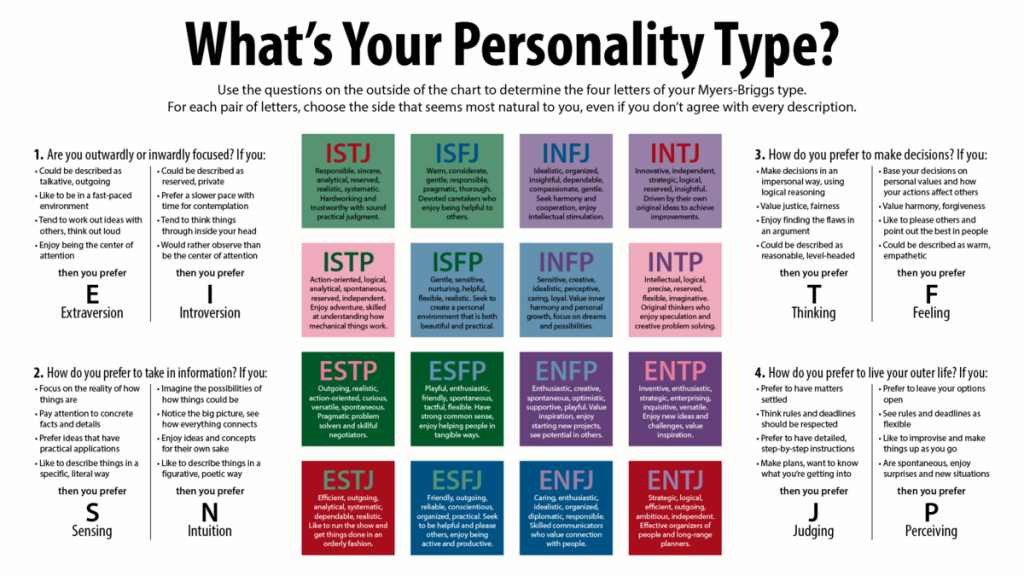

Write as many descriptive words for their personality (eg. blunt, subtly manipulative, talkative, etc). The Myers Briggs personality indicator is really bad pseudoscience but it can be a useful schematization for the purpose of character creation:

What are their flaws?

Flawed characters are a must in contemporary TV and movies not only because they are more realistic and relatable, but also because their journey is very often about struggling or coming to terms with their flaws, becoming better people or trying to do so.

Eg. Matrix’s Neo and Shinji Ikari have to believe in themselves to become the hero, and that’s what drives the story.

Follow up: where do their flaws come from? Was the character hurt or traumatized? What’s a convincing backstory for this important trait.

What is their strength?

Great characters, especially protagonists, show strength of will. In all their flaws they are willing to make difficult choices.

Eg. Elliot is willing to go to any length to save his friend E.T.

Follow up question: what’s the force that drives them to make tough decisions?

Follow up question: how is that strength leading your character toward danger and hardship?

A classing dramatic question: what’s the worst possible thing I can throw at my protagonist?

Pretty classic motivator: hero wants to revive girlfriend, makes a morally dubious deal with supernatural entity.

How can you introduce the character?

What’s a character-defining moment that immediately reveals some aspects of their personality and background?

E.g. a messy student in a comedy could be late for class, bumping into people and dropping papers. A rich protagonist could dress elegantly and drink Champagne, the hero saves the cat in the first scene…

We hear the couple in Facade having an argument even before seeing them. If you knock at the door Trip immediately put up a “facade” and welcomes you.

These examples are in the realm of tropes and stock characters, so what’s a strong, more unique entry for your main character?

What are they doing, right now?

It’s very common in games to see NPCs just hanging around waiting for the player to show up. Give them a reason to be where they are, an activity, a purpose.

-

Define the dramatic question

A story (and a story driven game) should have a central dramatic question. Write yours down. Examples:

Is Odysseus going to make it home from Troy?

Will Romeo and Juliet ever be together?

Will Michael Corleone save his family?

The dramatic question should reverberate in each scene. Each scene, including the dialogues, should have a smaller dramatic question. If they don’t they may feel unnecessary or boring.

Will Odysseus outsmart the cyclop?

Will Romeo and Juliet kiss?

Is the Mafia deal going to be made?

Write down yours for this dialogue.

-

Define the character’s arc

Almost all character-driven storytelling involves some kind of change. The main characters “develop” over time: they conquer their fears, overcome obstacles, address their flaws, find their place in the world etc… This journey is referred to as the character arc.

Think about the transformation you’d like to see in your character and identify the key moments in which they gradually get to that point.

-

Define their relationship

Characters rarely exist in isolation. Think in terms of the relationship between your characters, and relationship arcs, rather than only as individual characters and character arcs.

How do the characters know each other?

What’s the power relation between them and how is communicated in the dialogue?

How can you challenge or shift the power relationship over the course of the dialogue?

Imagine your characters at a party, would they get along?

Imagine the characters in a difficult situation together (eg. on a sinking boat, having to confess an affair). How differently would they react?

Katamari Damacy wouldn’t be as memorable without the protagonist’s relationship with his hard-to-please father.

NITW is not just about the coming-of-age of the protagonist Mae but also about how her relationships with friends and family changes over multiple encounters.

-

Define the conflict

The dialogue should present some form of conflict. If the characters completely agree or one character is just there to provide exposition or bits information, it can result in a classic Bad Videogame Dialogue.

Some types of conflict:

A direct argument

If two characters are fighting they are likely to be in an emotional mode of dialogue: contradictory, emotional, not well articulated.

You can have diverging intensity between dialogue modes, one character can be upset and the other indifferent, reassuring or apologetic.

Struggle against circumstance

Eg. stranded in a desert island, locked out of the apartment.

Internal conflict

There is an unfulfilled desire. Find a way to externalize it, in words and actions, but not directly. The character may not realize what they really want or not be ready to confess it. That’s why it’s internal.

Avoiding a negative outcome

Eg. I have to break up with my partner without hurting their feelings, avoid embarrassment. I have been caught lying and I have to justify myself…

Confusion

Where am I? What’s going on? (eg Matrix, dropped in a foreign land, fish out of water setup). The confusion can’t last for too long or it can be frustrating to the viewer/player.

Flirting

Not necessarily a conflict but a good way to practice subtext: communicating hidden feelings or motivations without expressing them directly.

Persuading / Manipulating

A milder kind of conflict, that presumes different initial goals or a disagreement.

Dilemma

The characters have to make a choice but all the options are bad.

The conflict should not reappear in the same terms over and over. The characters should not have the same argument repeatedly, the conflict should change or evolve. Each subsequent conflict should change the character somehow.

Pick one or more conflicts that make sense for this dialogue.

Every passenger conversation in NeoCab presents some type of conflict, often involving differing opinions on the cyberpunk city you live in. There is an internal conflict between what you would like to say and what you shouldn’t say in order to not lose the client, and conflict incorporated in the game logic, your character’s mood and stress level can block certain dialogue options and preclude some story branches.

-

Define the stakes

Make sure that is clear to both characters and the player what’s at stake in the scene. If something happens or is said, what are the consequences, what could be happening next. What are each characters’ ideal outcomes?

In real life most conversations are not high-stakes. Movies and games are more likely to represent extraordinary moments, days in which the character’s life will change forever.

Some example of consequences:

A decision is made

A question is asked

Information is revealed

Momentum or tension is built

A character’s viewpoint changed

Beware of completely resolving conflicts between characters, as it might reduce dramatic fuel.

Not all choices in 1979 are truly branching but the high stakes are always clear.

Let’s start writing!

You will write your conversation on your discord. Each team member will roleplay as one of the characters.

Indirect dialogue (the teacher told him to study harder), thoughts (I instantly fell in love with him), and narrator voice (they hated each other immediately) are all valid techniques, just make sure agree beforehand of what modes and formats are “allowed”.

Over the course of the exercise I’ll throw in some challenges you can integrate in the next lines of the dialogue.

If the conversation appears resolved or there’s nothing left to say, just start a new one with different premises or characters.

Some more tips and checkboxes:

No monologues

Write in very short sentences with lots of interchange between the characters. People rarely do monologues in regular conversation.

Does it sound like something people would say?

It can be awkward but try to say your lines out loud before pressing enter.

Avoid stating the obvious

Particularly in respect to things the player/audience can see or hear. Avoid repeating the same bit of information twice.

Do characters have unique voices?

Can you take a character line and give it to another character? Or are they speaking with the voice of the author or as a generic archetype like “the cop”.

Are the characters speaking for themselves?

Is the character saying what “they” want to say or what you want to say? Is the character expressing their own feelings or are they saying what’s needed to move on with the scene, to get to the story point?

This is harder to do in games because of the utilitarian nature of players’ interaction.

(Adapted from Scriptnotes podcast ep. 37)

Challenges and modifiers

Add subtext

Make a character express an emotion indirectly.

Players/readers can be bored by dialogue that is too “on the nose”. Don’t ever have your characters say things like “I am sad” or “Luke was sad”. There are a million other ways to suggest that through words and actions. It’s even more interesting and realistic when the characters are trying to hide their feelings.

Eg. A scene may be about a couple shopping at Ikea, but through their excessive argument over curtains you learn that their marriage is in trouble.

Take the dialogue from Parasite page 103. The rich couple is talking about the smell of the working class protagonist.

The subtext is their classist disregard for the protagonist but it’s much more compelling because they deny it’s “poor people’s smell”.

Some dialogue modes that can carry subtext: passive aggression, flirting, overreaction, sarcasm, misunderstanding.

Have your characters listen to each other

Have your characters actually listen, engage, interrupt and react to things said by each other, instead of each character just speaking because it’s their turn.

Sometimes adding discursive markers like “so”, “but”, “right”, “well…” helps connect dialogue lines.

“So, it’s like Uber for golf carts.” – completing a thought.

“What’s more, there’s no evidence he even read the book.” – the “what’s more” helps connect with what has been said before.

“No, you’re right to be concerned.” – the “no” means: yes, I see what you are saying.

Add another sense

Your characters have a body and perceive stimuli beyond the audiovisual information shown to the player. Add a non-random note about something the player can’t perceive. It can be an interior feeling resulting from an emotional state. And yes, there are more senses than the famous 5.

Yes and…

Mention/reveal a bit of information about the character or the world that wasn’t previously defined. Force your teammates to respond to it.

It’s the famous rule of improvisational comedy: accept what another participant has stated (“yes”) and then expand on that line of thinking (“and”).

Undermine

Try to undermine the other character’s line of thinking. Depending on the context it can be confrontational, manipulative, an interruption or an unwanted digression.

NPCs have questions too

To counter the NPC as an information ATM, make them ask a question to the player character.

NPCs have lives too

Allow characters to exist offstage and not only to serve the player. Reference their background lives and interests, at least those aspects worthy of mention, in their dialogue/character interactions.

Add idiosyncrasies

Each person speaks differently and has their peculiar mannerism, sentence constructions and catchphrases related to their background. It can get gimmicky or exhausting if used too much (e.g. Yoda’s way of speaking works only because he’s not the protagonist).

Jett features a made up spoken language and subtitles using implausibly formal constructions and archaic terms, suggesting a difficult translation.