Ideation & Brainstorming

We started with the one question: how can we take advantage of the community spaces on campus in order to create a playspace fitting for a new game? Our solutions varied between very different approaches. One set of ideas was to acknowledging the “class wars” culture between majors at CMU by re-inventing the spaces at Carnegie Mellon to become something like an airport, where certain users (majors) have special access. Other ideas that our team members came to the table with involved spontaneity, interactivity, and simply entertainment.

Our team settled on one idea on the basis of concrete planning, genuine excitement, and relevance to course content. This idea was to transform the walkways of CMU into highways and streets via chalk, inviting passersby to engage in the experience of mimicking a car’s actions by obeying traffic laws and driving together with your peers. Due to the lack of competitive nature for such an exercise, and the heavy reliance on mimicry, we brainstormed more ways to add to the experience by focusing on vertigo. Ideas included making cardboard cars for people to put on and drop off from points A to B, to play upbeat, radio music on a bluetooth stereo, and to have some team members wear orange jackets with whistles and use loudspeakers to project the rules. Though the cardboard cars idea was abandoned due to the decision to prioritize “ease-of-entry” into the game, many of these tactics to create a more immersive experience stuck around.

Prototyping

After the team convened to map out the right location for road transformation and deciding on what road signs to make, we set out to playtest.

Certain aspects of road transformation we focused on were quality of chalking, resource limitations, and how bystanders adhered to the new lines. The quality of chalking was a primary focus because we believed the more realistic the road-lines appeared to be, the more interested people would feel in getting involved. We tried different designs for the yellow, middle lines and agreed that one solid, dashed line up the middle looked most realistic and saved us chalk. We got a good idea of how much chalk we’d need to gather. Finally, we noticed that bystanders didn’t care too much about “staying in the right lane”. Many folks passing by didn’t seem to care much, and were walking on whatever side. The insight we gathered from this is that we would have to be more keen towards making the rules on how to play the game very visible, and interactive. Maybe the road signs could only be used for the rules, or possibly we could hold the signs and read them to folks passing by, asking if they would like to play the game.

The final aspect to our prototyping face involved walking around The Cut, imagining that many of the walkways were sketched as roads, and playtesting our game. We wanted to test if it felt awkward to walk around with our hands up, and see if the rules we designed were realistic and fun. A summary of the insights we gathered were that yes, it is awkward to walk like that but is less weird in groups, and there were too many rules to be accounted for (person with red shirt means stop, person with green shirt means boost, person with white shirt means pull over, etc.) and so they would need to be consolidated to increase ease of playing and reduce confusion.

What We Did

In preparation for the big day (Thursday 9/21/2017), we completed three important steps: re-defined the ruleset, implemented a marketing campaign, and set up the playspace. The ruleset was too complicated and thus too confusing for people to jump in and play, so we narrowed it to three simple rules.

-

To play, hold your hands up like you’re holding a steering wheel

-

Stay in right lane

-

Stop if someone in a red shirt passes you

We agreed on this ruleset thinking it would find the happy medium between enough rules to be engaging and not too many rules to make it easy to play.

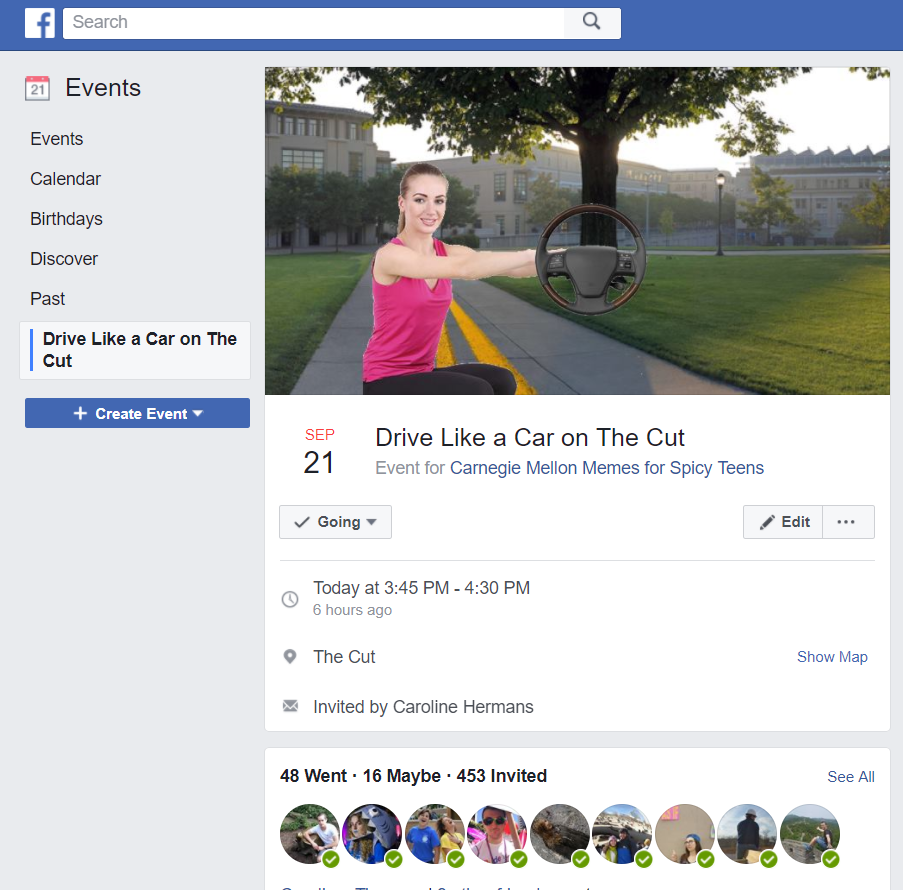

In terms of marketing, a Facebook event was created and publicized to a popular group of Carnegie Mellon students. Our main goal here was to give people an idea of what the game is before arriving and maybe even get some folks excited about playing. Below you can see the event page from Facebook.

Finally, we set up the playspace. On the morning of, at around 7:45am, we chalked the walkway going from the UC to Doherty. Two signs were made to post the rules of the game in a quickly readable way. One rules sign was tied to a tree at the first entrance, while the other was stored away to be used later in the day at 3:45 when the game would begin.

What We Expected

We expected people to be open and receptive to the idea. We expected it to work something like 99 tiny games, where people would see a fun intervention and think “oh cool!”

We wanted it to be something that wouldn’t distract anyone from their goal, which is walking between buildings. We made it easy and tried not to make too many rules so that people would feel like it was a fun intervention into their daily routine.

What Actually Happened

Most people were disinterested in the game. People found it weird. A few people played along, mostly our friends. It wasn’t clear that it was a game to a lot of people – they weren’t sure what our intentions were.

People didn’t feel comfortable expressing themselves in public.

Some potential sources of ambiguity were that people thought we were protesting because we had signs. One person even commented that they thought we were trying to promote safer driving. Because the game had no clear objective, it wasn’t clear to people that it was a game.

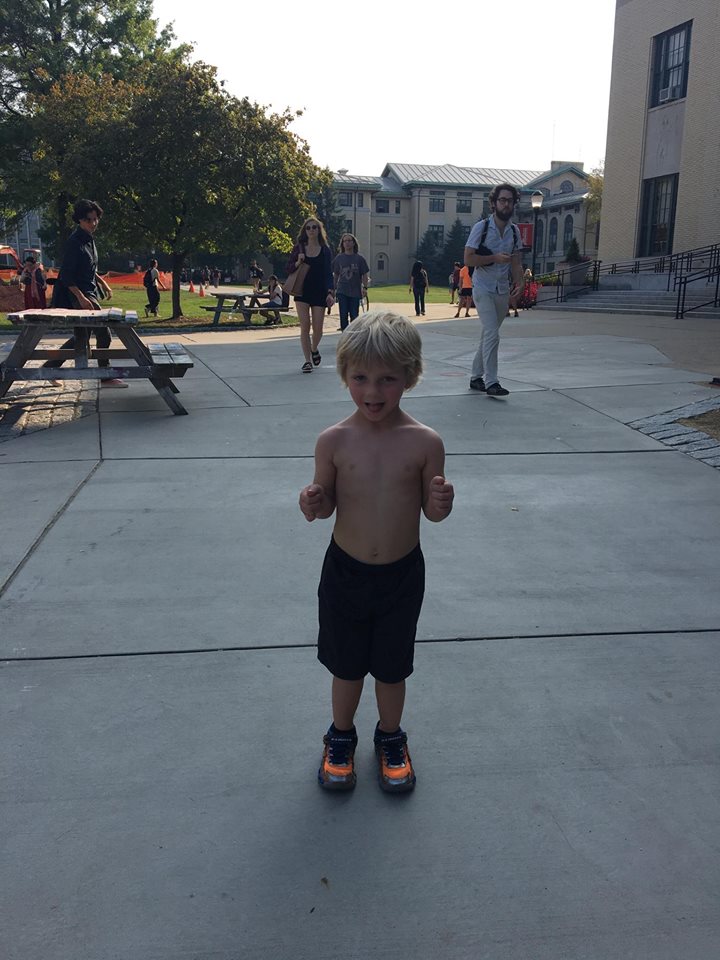

That said, there were a few shining moments:

What We Learned

- If you’re asking people to play a game, it needs to be obviously a game

- Don’t make people embarrass themselves

- The magic circle should be a safe space