Inquire about artificial intelligence here.

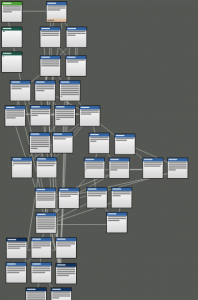

Created with InfiniteAmmo’s Yarn.

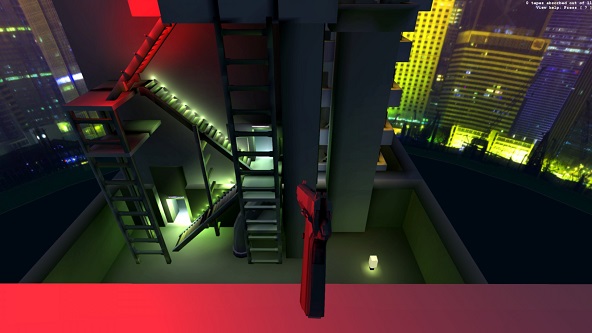

Assignment 03: Virtual Character.

Created by John Choi.

[Note: Unity Webplayer does not work on Chrome.]

Inquire about artificial intelligence here.

Created with InfiniteAmmo’s Yarn.

Assignment 03: Virtual Character.

Created by John Choi.

[Note: Unity Webplayer does not work on Chrome.]

Christian Murphy

10/14/15

A game that used environmental storyteller extremely well was Battlefield Bad Company 2’s online multiplayer. Back before DICE and EA pulled all the environmental bullshit of BF3 and BF4… BF had fully destructable environments in the Bad Company series. This meant houses would lose walls, windows would shatter, trees would fall, and ultimately entire structures would collapse killing everybody inside.

This was immensely powerful for an online war game, because it showed the routes of battle. The game mode ‘rush’ has players defending bomb sites, while attackers went to set charges. Because the size of the map, parts of the environment would remain untouched while others would see heavy battle.

It was visceral to see how lobbing several grenades into a house would send bodies flying out, and simultaneously collapse the roof destroying the cover provided. It also added to the strategy of the game as snipers could crawl across the rubble and hide amongst the ruins using the dust to cover their advance. In the Vietnam expansion this was expanded with flamethrowers destroying jungle terrain, and ancient ruins being toppled by invading marines.

I thought this mechanic created near endless environmental stories. As you spawn into captured territories, the land is littered with rubble and destroyed gun emplacements. Even though bodies disappear for system performance, the landscape speaks to the struggles that players have overcome, the burnt out tanks, scarred roads, and ammo packs of dead soldiers.

I remember one specific time where this environmental technique was incredibly effective. We were raging an intense battle over the second last point in a map. Snipers had lined the ridge blocking any potential cover to get to the spawn point. Everything had been destroyed except for one house. It lay in a field of rubble as the other 5 houses had been leveled by explosives and tank fire. After we eventually counter sniped the enemy, but only had a handful of men left who took the point, the only thing standing was this one house. When we narrowly won the match and the camera flew around the battlefield, I was reminded of our close victory by seeing this structure. The battle could have gone either way.

Notes on Walking Simulator

What Happened Here? Talk on Environmental Storytelling

ecology of storytelling

item and enemy placement

Physical boundaries

Staircases, walls etc

restrictions create meaningful interaction

“The Imago Effect”, which covers the subject of how identity is in part performative and part shaped by context.

use player context to bring meaning to environment (booze, cash register, stripper poles)

“We’re saying that the game environment, which has been derived from a fictional premise, can communicate • the history of what has happened in a place • who inhabits it • their living conditions • what might happen next • the functional purpose of the place • and the mood.”

Images of environment makes player ask- what happened here?

Telegraphing: Foreshadowing gameplay elements by using the environment

blood leading to doorway

body electrocuted on fence

Important part is what environment alludes to that we don’t see

Child slave den for torture Fallout 3

interpretation is compelling

builds investment

provides closure

Process of making a good environmental narrative

Echo: Relating to the larger societal construct of the world

Player leaving visual mark on world because of their action

The Not Games article makes a good point, and I agree that more developers should explore different genres of games. However, I found what they were saying to be a bit over-the-top, i.e. “Despite a few noble attempts, overall, videogames are empty systems that only serve the purpose of wasting time.” This might be because the presentation was written in 2010, but I feel like a lot of what they are complaining about is already changing. There are a lot of indie games and even Triple A titles nowadays which seem to be exploring a lot of the ideas that the Not Games authors were urging people to explore. Obviously there is still a lot of shovelware and generic first person shooters being released, but in the recent years there have been many new explorations into other types of games, making the article seem a bit dated.

Also I find statements such as “videogames are not games” seem to be kind of used for shock value. The authors claim that because we obsess over video games and spend hours on them they have become more engaging than other non-video “games.” But this isn’t exactly true. The authors mention Chess and Go as actual “games” in contrast to video games, yet some people do devote their lives to learning all the in’s and outs of these games and becoming champions at them. In trading card games such as Magic: The Gathering, this obsession and devotion is also apparent. The same goes for physical games such as sports, and the process of becoming athletes. In these cases, these individuals “obsess” over and devote hours to their respective games of choice just as video gamers devote hours to their video games of choice. Also, some video games and some video-gamers don’t devote hours to playing games. Some people like to play quick 5-10 minute games which may or may not have replay-value, or mobile games, which also are generally very quick to play at a time. So, since there are non-videogamers who devote a lot of time to video games, and videogamers who don’t devote a lot of time to videogames, I don’t really think their distinction between “non-videogames” and “videogames” is really that accurate. There are a lot more blurred distinctions than the authors would make it seem.

For something more to chew on for notgames and Tale of Tales, and why they have abandoned videogames. As much as I hate gamers too, I don’t think it’s right to reject and blame your audience for “not understanding your art.” Sometimes it doesn’t click with people, and maybe the world isn’t ready for it yet, I don’t know.

For environmental storytelling presentation: I was rather disappointed they only covered 3D games with free camera control. They said that video games can’t exactly apply the same film set design concepts because filmmakers use directed eye, but that’s not the case with 2D games or 3D games without free camera control. Even 3D games with free camera control still uses level design to direct the player’s eyes to certain elements–isn’t that part of set design? Basic film concepts still lend themselves well to videogame scene compositions, especially games like Kentucky Route Zero or Papers, Please.

That said, the first time I actually became conscious of designer/narrative intentions in environmental storytelling in video games was Portal 2. In this level, you happen upon a room full of potato-related science project presentations. If you read into these and have been invested in the narrative so far, you learn several things that aren’t necessary to further the plot, but deepens the narrative. Not only does this room expand on the game’s frivolous but creepy tone, but it also gives you a flavor of the narrative if you were interested, if the player was inclined to give some of her time to the game to explore. It’s left quite the impression on me and it’s the reason I prefer Portal 2 over its predecessor even though the latter is arguably a better game.

In the presentation Over Games, I found the point that “Games Are Not Art” interesting and rather funny, being the fact that I am taking this game design course as part of my art degree. The presentation makes the statement that gamest are intrinsically created — that “people have been playing games for as long as they have existed.” By presenting this information, the presentation implies that art is not born of this intrinsic need, whether it be medical, psychological, or social. Games have rules. Art does not. You can “win” a game. You cannot “win” in art.

While I agree that these differences are distinct, there exist games that can crossover into some kind of artistic expression or as an artform in many ways. Game mechanics and play cannot be considered as fine art, or anything that is simply well-engineered can be considered “great art”. Otherwise, the complex rules of Go or football can be considered “fine art.” Therefore, we don’t consider great players of Go “artists.” We don’t consider the great players of football artist; they are great athletes.

What set video games apart is the dual nature of both gameplay and narrative, the combination of play with an immersive “alternate reality.” This is what sets video games apart from sports and commercial card games, which do have gameplay but arguably not the same level of immersion. No one would argue that a game of football is “art”, yet fiction in both film and literature is widely considered as a form of art. Games can be art because dramatic/narrative elements can convey artistic thought. Games are creative. Legally, they are afforded legal protection by the Supreme Court as creative works.

However, the boundaries are still unclear. Is art just consisting of observation (you observe a painting, drawing, etc. traditionally)? Can art be interactive or immersive? I believe with the acceptance of the rise of New Media as an art (as well as interactive installations), video games can be considered as art simply if they reach a certain “threshold” of being immersive. But what is that threshold? If someone considers Super Mario Bros immersive and engaging, is it then art? And then, what is the threshold of literature and cinema being considered as an artform. In those mediums, there is also a sense of distinction between movies that are considered “art” and those are not, literature considered “art” and those that are not. Critically acclaimed films are considered to be “fine art”, but no one would claim Twilight as “fine art.” Again, widely acclaimed literature (including “the classics”) are considered an art form, but trashy romance novels and most young adult books are not. Perhaps there exists such a distinction in video games. Or is there a difference between “video games” and “art games”? Another additional layer to consider is the difference between commercial games created by the game industry in comparison to “indie games.” Are video games considered art because of progressiveness or certain elements with concept? And so the debate keeps going…

I found it interesting that sandbox style games were not mentioned in any of the articles about “not games”. I understand that sandbox style games are not walking simulators, but from my understanding they are also not games. During discussions of games in other classes and outside of classes it’s always been the case that games were defined as having a goal whereas toys were defined as not having a goal but supporting emergent goals and having interesting interactions.

Walking simulators are interesting in that they give the player the ability to explore and find the secrets and the intentions left behind in the environmental style stories by the creators. I would go as far as to say that some sandbox style games allow the player to create their own stories. And while not everyone’s story is not amazing, both sides of the creation and consumption dynamic can be fun if the player is given the correct amount of agency.

Expanding on this, I think at a higher level this is the core dynamic of all interactive stories. The creator decides on (or is restricted to by time or money) some amount of agency to give the player, and the player gets to experience the story in some bound determined by the agency given. Higher agency tends to yield less cohesive stories, and less agency tends to yield more cohesive and complex stories, but with less interaction.

Within the presentation given at the Art History of Games symposium, Over Games, Auriea Harvey & Michaël Samyn explain “For both the creator and the spectator, art is an exploration of the self and its environment.” This too seems to be the primary case for the arrival of the walking simulator. Game creators endeavor to build a virtual environment that enables an immersive experience rather than to perpetuate a competition or end goal. The video game is no longer a game but becomes the medium for artmaking. Games such as Dear Esther, Gone Home and The Graveyard champion such simulation goals. In the past and even today, walking simulators are not largely accepted by the gaming community. Their player interactivity is generally limited and thus controversy has surrounded their very notion. Screw Your Walking Simulators protests “sitting, walking, listening, looking, playing, just fucking being is interaction”. The games provoke the idea of what it means to use a videogame. Participants inhabit the spaces, explore, and the intentions of the game are left open-ended for the player to navigate. Storytelling transpires as players move through the environment and understand space.

I enjoyed the metaphor of walking simulators as “secret boxes,” or a Japanese toy whose beauty lies in the secret motions and movements to open it. There is nothing inside, and really not much of an ending to these games. Yet the narrative arises from the journey and interactions of the player.

While many of these exploratory games come up with amusing interactions, I feel that there are a lot of pitfalls. Point-and-click games with “pixel hunting” (searching for a specific pixel to click on) can often get tedious. Personally, I found Gone Home extremely repetitive: despite a brilliant story, rifling through drawers and cabinets for every single detail got old fast. Sure, the storytelling was solid. But the game itself was BORING.

I believe the key to secret boxes is novelty. Secrets are no longer secrets if they’re constantly repeated. Instead, beauty arises from new and creative ideas. Amanita Design’s Machinarium and Botanicula are good examples of secret boxes that always provide new areas to explore and new objects or creatures to interact with. By constantly designing things the player hasn’t seen before, one can build a great world. That, I think, is the key to a secret box.

Walking Simulators: Thanks to the Gamasutra article, I finally feel like I see fully where the interactivity lies in so-called “walking simulators”. With that in mind though, the genre name “walking simulator” does not seem appropriate at all. If the point of these games is to tell narrative by exploring the environment, then these games are not at all about walking. But, the fact that most “gamers” would label these games as “walking simulators” is telling.

Almost any game design class or textbook will begin with trying to define “what is a game”. They’ll go through the timeless rituals of adjusting the definition to be broader or narrower, and eventually reach a much more nuanced and thought out definition. For all this though, it seems like in practice, even game designers will throw out these carefully thought definitions for a few heuristics that describe what the Industry thinks a game is. For example: “Can I win or lose?”. If a game doesn’t contain the ability to do this, many people, even game designers, will label it as not a game. I know this, because I worked on such a game at the Global Game Jam, and this was people’s reaction to it.

Gamers think of games by how you manipulate the game state (i.e. moving in-world), and how you win. So, if they looked at a game like Dear Esther, it’s no surprise that the only material thing they would see to “do” in the game, the only obvious control, is walking. This goes with my reaction to the notgames article: that the industry’s mindset on games is so ubiquitous, that it is hard to even think outside of it.

When I was playing HerStory for this class, one idea stuck with me – the fact that the sole reward for playing was also the sole mechanic by which you played the game (watching videos and uncovering the story.) There was nothing beyond watching and searching for videos. The entire game was literally nothing more than the backstory – but the interactivity that dictated how this backstory was presented made a massive impact on how the game felt. I strongly agreed with a lot of the tenets of “notgames,” most of all this idea that videogames are defined by their interactivity, and that by utilizing that interactivity, a videogame can become much more than any old ‘game’ or other art medium.

I made a post for the last discussion about how the tactile interactivity of the original version of Sword & Sworcery influenced how I perceived the game – I felt that having to touch the screen made me immerse myself in the game’s environment more than merely clicking would. Another aspect of S&S that I loved was the reversal of the standard ‘growth with progression’ trope found in games like the Legend of Zelda series, where you gain items and health capacity after each boss. In S&S, your max health decreases after each ‘boss’ instead. This reinforces the theme of self-sacrifice that is core to the story of S&S, and further immerses me as a player in the game. The player character is getting weaker as their quest takes a toll on their body – it makes sense that the difficulty should increase proportionally.

Overall these design choices added so much to S&S and allowed me to experience the story and themes in a way I wouldn’t have been able to otherwise. S&S was the first game to make me think about how these small design choices could decide whether a game is amazing or awful, which got me interested in game design. The GDC presentation on Environmental Storytelling put a lot of my thoughts on game design into words, and I’m glad to have it as a resource to refer to from this point forward.

I resonated with the notion of notgame, but the world’s not ready for it. Even at CMU I find there are people who hold staunchly to the separation of art and game, based mostly in their inability to take a game “seriously.” And of course, if your AAA product tries to be meaningful, its commercial ties negate it effects. This is a problem I find in interactive art in general. I talk about my work as “interactive systems/objects” rather than games and toys. When framing an artwork under “game/toy” as a tool of exhibition, I often get viewers (which I define as those who critique and gaze) who refuse to be players (which I define as those who critique and interact) because, “you don’t touch the art.” I have to put up a sign telling people to play, which introduces language (which is a whole other animal) and authority over the work, or I have to beg, really beg, in a statement (which, let’s be honest, no one reads) to get the viewer to make that leap. To accept “permission.” At the moment though, inhabiting that in between space of “notgame” is tricky, because I feel like only those who like/make similar works currently understand what that means. An uneducated viewer will default to whatever they are most familiar with and critique the work along those norms. This can work for games/arts that use these expectations to their advantage, works in the relational/antagonistic aesthetics/social/political genres. However, works that don’t use those conventions are still up a creek in terms of acceptance. Changing this is a matter of world view. In Tale of Tales spiel, they speak of how Modernism destroyed everything regarding the acceptance of the divine conundrum (The simultaneous acknowledgment that creation is an act of divinity/ transcendence the practice of creation as a human.) They speak of how a world view changed perception, and how they wish to change it again. But I don’t think a single person can change a world view. That’s what makes it a world view. Yes, there will eventually come a day when these distinctions and defacto rules around rule systems are no longer present. When no one will care to categorize what you made, because the fact that you made it at all at the time you did will prescribe meaning to it. It’s silly to think that a work’s value is solely put in place by those who write articles on it. However, right now the notgame distinction is necessary to rebel against other interactive system definitions so that the idea can later be assimilated into a spectrum and cease to be relevant.

Best played with sound

UPDATE 10/19/15:

Unpacked images and .zip for easy play

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B-YvMeeemTlWVkgxQmoxNEgxeG8&usp=sharing

OUTDATED:

Added facial tweaks fixed bugs

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-YvMeeemTlWQ2tlWVVxaWhXb1U/view?usp=sharing

Some animations so don’t be too click heavy, let transitions play out

OUTDATED:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-YvMeeemTlWTm95TzE3RV9udGM/view

It is a game about a gem and the people it meets. In sum, there are three characters the gem can meet, a boy, an alien, and another gem. Created by Qiaochu (Mac) Li.

Update: A quick fix for the alien crush bug.

A reflective journey into space for a sick, old man’s dying wish.

Character art by Crystal Hou.

Background and music in credits.

A game about a dead woman, a live orphan, and the legal grey area of resurrection.

www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/gdebree/Maryam-1.0-all.zip

Mystic South: Irma

Issues have been addressed, here’s new builds.

A woman visits the matriarch and patriarch of her community to abandon her daughter.

Note: There is sound. It is very important.

Note #2: I made this in Unity, because documentation. To play this game: 1) Download the zip file appropriate for your machine: Mac or PC. 2) Unzip. 3) Double click the executable. 4) A window will pop up. Set the drop down menu to your screen resolution. 5) Profit?

Reading about the way Eliza functions reminded me of the game Façade. Being my first experience interacting with characters via keyboard comments, I was really impressed by how intuitive and smart each character in the game appeared to be. I had assumed that Façade relied on a series of keywords the user might type, in order to generate those compelling responses but I didn’t realized that this type of text based interaction between the user and the computer has had such a long history. In that sense, I’m surprised by how little it has evolved within the gaming industry. I mean, side scrollers have evolved into completely 3D landscapes, sprite based games have evolved into full scale, open world games and point and click shooters have evolved into well, shooter games. I’m just surprised to see that text based games seem to have remained stagnant in that sense. I wonder if this is because of the more graphical nature of the other gaming types mentioned. I mean, though all of those games have evolved graphically, conceptually they are still the same at their core.

I think that maybe because text based character games like Eliza rely on the one on one dialogue between the AI and the player, an evolution for the form hasn’t emerged in the same way as the other forms of games. I mean, now we have voice acting but unless the technology behind voice commands and reading them evolves in a more intuitive way then typing things on your keyboard or selecting text through your game pad, I don’t see the genre really moving forward. Also, because character and user interaction with said character is important, I think it would be a lot harder to make a game with a variety of characters—with their own personality and ticks—within such games. RPGs and dialogue based games try to flesh out their characters, and do so more than other games, but at the same time they are not nearly as intelligent or unique as characters like Eliza are.

In this non-linear chapter based narrative, the player character changes at each chapter, not the characters the player interacts with. There are two chapters planned, each revolving around Irma and Iris-Jane, twin sisters, visiting the elderly leaders, Mr. and Mrs.Oseye, of their community of Mystic, Alabama (fictional.) The language of the game will follow the vernacular of it setting, and the Oseyes will change in appearance depending on who is approaching them. They are a manifestation of the force of death and guardians of the door of the afterlife.

In one chapter, the player character is Irma (the player never actually sees the visuals of Irma) and is dropped in to the scene as she approaches the Oseye house with her infant daughter Sarah. The elderly couple reveal to Irma that her sister is coming back into town, and Irma spends the rest of the chapter wrestling with her rocky relationship with Iris-Jane. In the end, Irma may decide to welcome her sister into her home or cast her out.

In the other chapter, Irma again approaches the Oseye house with the infant Sarah, but is met with hostility and disappointment. Through dialogue choices, the player may or may not learn that Iris-Jane has murdered her sister and assumed her life. In the end, Iris-Jane may admit her deed and turn herself in, or Irma may continue to live with the guilt forever.

A. A distant descendent of the ancient Scissors clan, she is infamous in the RPS community for her incisive mindgames, improvisation, and lighting reflexes. She hails from South Bronx, raised by her single father. Having lost to B already, she has fought through the most fearsome opponents in the RPS World Championship losers’ bracket for the sake of her father who watches from his hospital bed. She faces her childhood bestfriend, now-mortal enemy again in grand finals.

B. Considered by many to be the greatest RPS player to have ever lived, he is the descendant of the ancient Rock clan. It is said that, were he not blind, RPS would be a theoretically solved game. He is known for his iron will, devotion to a fair game, and respect for worthy opponents. He was raised harshly by unloving parents who value their clan’s prestige above all, and taught to chop off a finger every time he loses a game. He is missing exactly two fingers: once to his father, and once to A.

The game is the dialogue between the characters just before they throw their hand. The player, as A, can shake B through a variety of dialogue choices, such as declaring her hand, predicting his hand, exploring their relationship or his psychological baggage, etc.

Most of the time, B will be able to predict A’s choice, but through the right path, it may become fair, or A may even be able to predict B.

Outcome 1: A wins fair.

Outcome 2: B wins fair.

Outcome 3: A throws the game.

Outcome 4: B throws the game.

http://www.flickgame.org/play.html?p=a0038dfd40c424d6b4ef

does reaching the end mean winning?

“I wanna go fishing. We should buy a boat.”

“We’re in the middle of the desert.”

“Details,details.”

Play all the flick games here

Then make your own. FlickGame

Make a little storyboard and a simple character study first.

No written dialogs.

No stick men.

Use a tablet. Go to the lab or check one out from the cluster.

Original characters.

Don’t include me in the game.

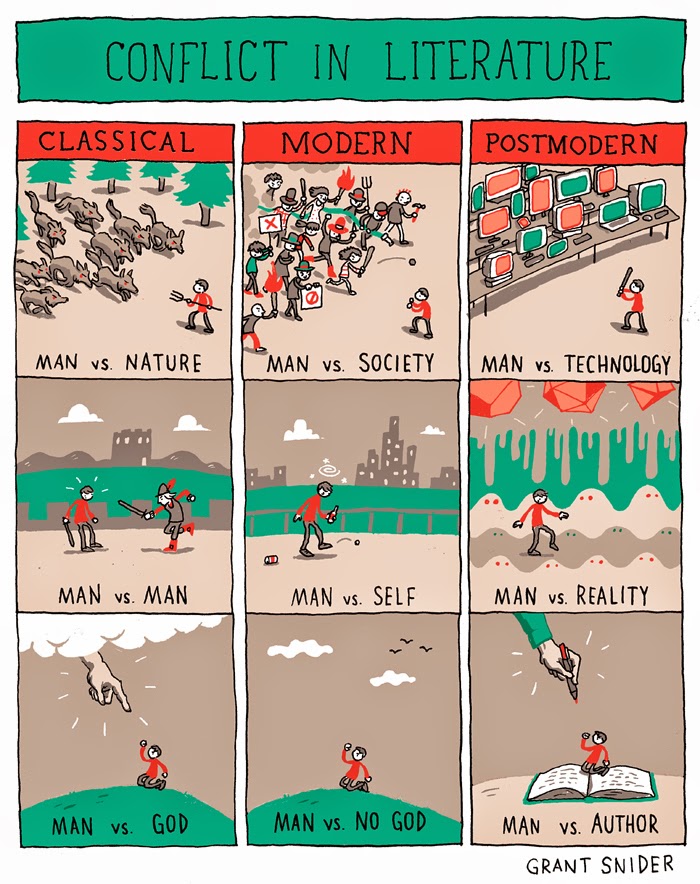

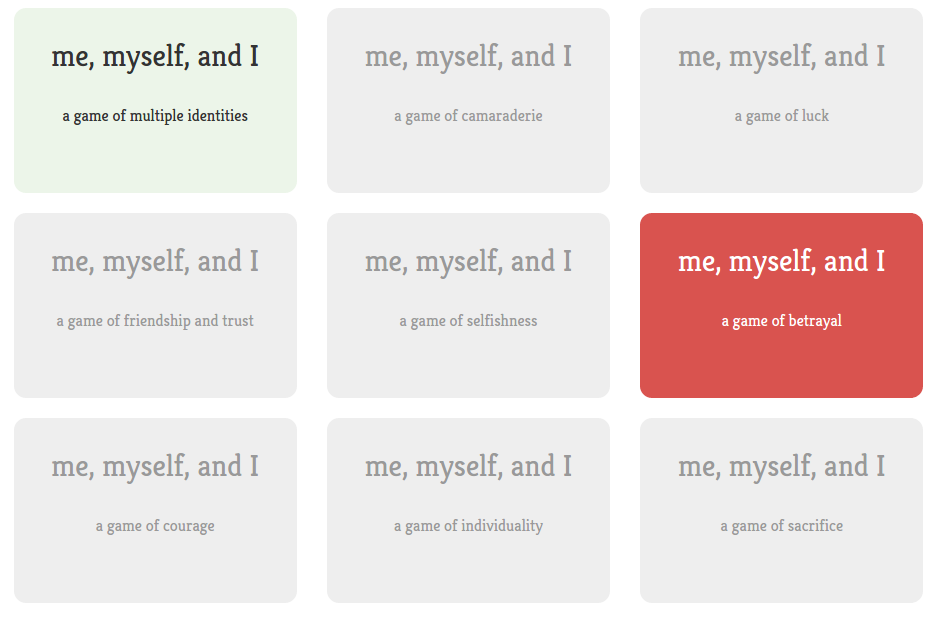

Pick a conflict from

Sword & Sworcery is a point-and-click game originally made for iOS. It has an amazing, almost etherial soundtrack composed by Jim Guthrie. While the soundtrack easily stands on its own, merely listening to it is not at all the same as experiencing it in-game.

Being a point-and-click game, on a mobile device, you must touch the screen in particular locations in order to progress. The game takes advantage of this – after melding the expressive soundtrack with the mechanical result of touching the screen, the end result feels almost cinematic. The mechanics of defeating a boss might just boil down to touching the screen along with the beat, but in-game, the Scythian swings her sword, clashing against the enemy’s projectile, choreographed to match the swelling music. This choreography gives Sword & Sworcery an epic feel, and the physical touch you make in order to enact this choreography connects the you as a player to the Scythian in a way that prose and other non-interactive forms of character development cannot.

When the game was ported to PC, touching became clicking, and I felt like some of this connection was lost. When clicking, you are no longer getting quite the same tactile feedback as when you touch the screen; you interact with the game through the proxy of the mouse pointer. The choreography still exists but its effect is slightly diminished. I suspect the effect might be restored if the mouse click were replaced by a key press, but I’m not sure.

tl;dr: The choreography of Sword & Sworcery combined with the requirement of physical touch in order to enact that choreography engages the player in a unique and powerful way.

So, I was thinking about simulation games (which we’ve talked about in class before), which is a kind of genre in games that I’ve loved since I was a kid — The Sims, Nintendo’s Animal Crossing, Tomadachis (do kids these days even have those anymore?), Farmville, etc. Because they are built on interactivity, these simulation games have literally boundless of potential for action and adventure, as well as for a relatively passive experiences. I think that the point of these games is to play a “new reality”, where you can make decisions where you otherwise cannot in real life. They give you a sense of control (which makes it extremely appealing to people who like to micromanage).

SPENT takes this genre of “simulation” and pushes it to the opposite direction.

SPENT is an online poverty simulation game, walking the player through the tough choices that unemployed people have to make. The question they pose is: Can you make it through the month? You are given $1000 to survive on. The goal is to survive with some money left over.

You have to get a job, secure housing after losing your home, get rid of your treasured possessions, decide which bills to pay because you can’t pay them all, and make other extremely tough decisions to simply just get by on a daily basis. Do you make a healthy meal or keep the lights on? Do you cover the minimum payments on your credit cards or pay the rent? Let your son play in the after-school sports league, or save the money that you would have to spend on his uniform? You deal with the shame and humiliation and sacrifices that comes with poverty.

This game was created by ad agency McKinney for non-profit organization UMD (Urban Ministries of Durham). The idea was spurred by the explosive popularity of other simulation games on social media like Farmville and Mafia Wars. They decided to make a simulation game that people can engage in as a powerful, learning experience about the reality of poverty and homelessness lived daily by people helped by UMD. The game is connected to social media (asking your friends on Facebook for some money, help, etc) which makes the game more personal — as well as a tool for more organic advertising. In 2011, McKinney and UMD also launched a petition to Congress to take 10 minutes to experience the challenge that more than 14 million Americans have to face everyday.

I think that it was a successful game. Of course, the game isn’t reality. It provides a somewhat slanted view of what it is actually like to live under such circumstances. Not all possible choices that are available for you in reality is possible in the game. And it’s obviously an advertising means for UMD. But I think that in the aspect of spreading awareness, the game succeeded. It is heartbreaking to experience. It is not a game you have fun playing. It was stressful for me to play. I think that it achieved it’s objective.

Although this game was essentially an advertising tool for UMD (after you quit or finish the game, you are asked if you are willing to donate $5 to provide a day’s meal for someone living SPENT), I think that it was a powerful conceptual game idea. I am interested in the idea of bringing the mundane, the everyday (or a sense of reality) into a game and expanding upon that to allow someone’s envision of the world to expand. I think that these kinds of games can be an exceptional tool to provide awareness of a problem that goes unnoticed or is ignored.

I’m probably the only person in this class who doesn’t actually play games regularly. Or, you know, ever. I took this class because I’m interesting in experimenting with educational games / using gaming constructs for other purposes. As such, I’m going to have to keep going back to the same couple of games I’ve played through completely: 5 nights at Freddie’s, Ib, Korra, Smash, and Journey. And now, Gone Home and the other assignments for this class. And because we’ve already discussed Journey in class, I’m instead going to focus on the other games (experimentally less interesting).

Ib

Ib falls into the category of scary/horror, which I wouldn’t usually touch with a five foot pole. Ib is made with RPG maker. You are a young girl named Ib who is taken to a formal fine art museum for her birthday. You end up along in the museum at night (although ify you complete the game alive you may possibly discover that is was your imagination, or any one of a number of different endings.) You have to try to survive the night, and you can choose who to help at what time – which determines who becomes your friend, who survives, and what situation you survive in.

The story is reasonably classic. The wide variety of endings is a great feature, if not original. But let me address one of the criticisms the game endures: the game looks like this:

Note the MS Paint style spray paint on the walls that don’t reflect perspective in any way shape or form.

Or this hand-drawn, awkwardly colored version of the protagonist (which is featured throughout the game). These graphics seem off-putting or unprofessional compared to other games. I recall when I played the first time I arrived at a certain stage in the game where you arrive in an area with the antagonist at this point in the game, Mary. The space is designed to look like it’s been constructed by a child, and the childish graphics add to the vibe in a really frightening way. From that point on, the game takes a “Clown of your nightmares” twist and anything that formerly appeared juvenile now seems doubly frightening, especially in contrast to the pixel art the barebones playable blocks of the game are constructed in, which is always perfectly geometric.

On the flip side, this game has such vastly different endings that you want to play the game over and over again until you find them all. In some cases it is evident when a certain action triggered a sequence of events. The choice you have to make are never clean-cut moral choices. The game might tell you that someone will die regardless of what you do, should you continue without them and try to save yourself? Then that person might be absent from most of the game and show up much, much later, usually altered in some way. This makes you reflect on your choices, as they cannot necessarily be blamed on circumstance.

Relatively recently I played a game called Papers Please. The idea of the game is you play as an immigration inspector for the fictional country of Arstotzka. The border is heavily guarded and entry into the country follows very specific rules due to post-war tensions. The player must inspect the documents that would-be immigrants present at the gate and verify that the information is correct and that the documents provided are sufficient to allow access into the country. The rules for which immigrants are permitted entry change due to changes in the political situation of the game’s storyline. Overall, as the game progresses and tensions rise, more and more paperwork is necessary to allow an immigrant into the country. Over the course of the game, a rebel group approaches the player asking for help. The player is also faced with a variety of other moral dilemmas including whether to let in individuals who have insufficient papers but some sort of dramatic personal backstory. The player themselves is underpaid and gets disciplined for mistakes, working to support a family with very little wage. The game has 20 different endings depending on how you choose to perform your duties.

One of the qualities that made this game such an interesting experience for me was that I found a strange sense of fun in the monotony of checking the immigration papers. While some might find this kind of gameplay tedious, I found it strangely calm and relaxing. Repetition and tedium is often seen as being something that should be avoided in games to prevent the player from getting bored or feeling unrewarded (i.e. repetitive grinding to get to level up a character without advancing the plot, etc.) However, repetition really worked to tell the story and set the tone of Papers Please. I guess because I’m a person who likes to organize things, something about the gameplay of repetitively checking and verifying these immigration papers was really fun to me. However, this sense of fun I got from the game directly conflicted with my tendency to want to resist the system. I thought it was interesting that I was enjoying the repetitive game mechanic (and therefore enjoying my job as an immigration inspector) so much, and yet the story I wanted for my playthrough was to align myself with the rebels and overthrow the government. By playing the game I was placed in an uneasy state in which I had to reconcile my enjoyment of the game’s mechanics with my dissatisfaction with the fictional Arstotzkan government, because I was having fun doing something that that government was forcing me to do.

There are a variety of games I was considering critiquing for this post, from Shadow of the Colossus, Mario Sunshine and Legend of Zelda Wind Waker but upon reflection I think the game that has really stuck with me is Detective Barbie: Mystery of the Carnival Caper.

Despite any preconceived notions one might have about a game staring a sugary sweet, superficial, plastic, commercial, action figure doll—Detective Barbie: Mystery of the Carnival Caper is a dark game. The premise of this game—similarly in Gone Home— is that Barbie, our main character, has just completed her time abroad at the Detective Academy. When she returns home, there is a carnival in town which her boyfriend, the illustrious, built and mildly dimwitted Ken is financially in charge of. At the carnival, Ken and the money raised for charity, disappear as a result of a magician’s act. This forces Barbie to search for her missing boyfriend, the money and the person responsible for their disappearance.

Unlike a majority of games “geared towards young girls” at the time, this was a game where the player (and main female character), has real agency.

I think one of the strongest elements of this game is it’s characterization of Barbie and its ability to build tension through the music and the slow pacing of gameplay. Never in this game do you dress up Barbie, or clean or cook as other games would have you do. Instead, you are constantly going from scene to scene, gathering clues, interviewing suspects and chasing (really the chase scenes were incredibly riveting in this game) the villain as you the go from area to area searching for clues from the disappearance using your handy magnifying glass piece together the mystery of the shadowy man responsible for Ken’s disappearance.

The unsightly characters, the haunting music and the eerie handprints and footprints that appear through the scenes really work to build the dark tone and atmosphere.

As a child, this game really struck a sense of horror in me, and now, whenever I hear the haunting music of a carnival, my blood turns to ice.

Oh, Ken.

When I played the Stanley Parable for the first time at my cousin’s house, I was struck immediately by the presence of the prominent narrator who narrates everything I am about to do, rather than what I have just done. The story telling perspective of a work of fiction is usually one of those details that is present in every story, but never thought about by a player. For instance, I have read countless novels in my life without knowing that there is a distinct between first person and third person, and the same holds for details of any field that are neither known nor noticed by a consumer, i.e. non practitioner. But Video Games are almost always either non-narrated or designed in such a way that the in game story tellers recall your past actions and exploits. Because of this homogeneity in narration form, I could tell that something was amiss when I booted up the Stanley Parable, much like when I am on accidentally on a satire site and gradually realize that the reports are not real. Since I am used to believing that I have control when I play video games, I naturally set out to fight the narrator’s decision making at every turn. I absolutely loved this mechanic of the Stanley parable and it kind of broke the ice for me in terms of new forms of art and story telling, kind of like how Bob Dylan or FLCL and many other Anime series tell stories through short references and a bricollage attitude towards synthesizing tales from fragments of culture.

I must say that the Narration Mechanic in the Stanley Parable is one of the most fascinating game mechanics I have witnessed this decade.

Life is Strange is an interactive visual novel with 3D graphics and a twist: you can undo the decisions you made using time travel. The basic setting of the story goes like this:

You are a photography student in a renowned art high school in Oregon. During one of the lectures, you realize you have the ability to go back roughly 1 minute in time to make the future turn out how want it to. Using this power, you can either choose to help your friends or subvert your enemies, and you save a best friend more than once. No one else knows you have this ability except for your best friend, whom you indulged with the truth.

The story setting is realistic in terms of the characters, their troubles and how they act – I often times found myself comparing my real life colleagues with the fictional lives of these characters. The principal likes to follow the rules, but sometimes following the rules is not the best course of action. There is a janitor who speaks softly and is really in tune with nature. There is an annoying all-star girl with a gang of cheeky followers who think they are the most popular people on campus. And there is also the son of a extremely rich money baron with some extreme violence and personality issues.

Your best friend has a step-father, who is the security guard of the school. This family is depicted as one with some real bonding issues. The best friend is rebellious, likes messy rooms, punk rock and anime. She also engages in all manners of dangerous and illegal activity, such as playing with handguns in junkyards and selling illegal drugs.

While playing this game, I really felt like I was fighting the main character for control of her future. Very often, she thoughts are spoken to the player, and those thoughts are always at odds with what I am actually thinking, and that also makes me want to strangle the protagonist. The choices we are presented with are usually ternary – in other words we get 3 choices in every situation. Despite this, even though you as the player have the ability to change the past, you can’t change the future. Many of the game major events have to happen no matter what. In essence, by giving the player a chance to change fate, they become the arbiter of fate itself.

I had killed thousands of lives in virtual world. I killed them using cold weapons in Mount & Blade. I gave them head shots in Call of Duty. I teared them into pieces by my magics in World of Warcraft. I killed them so I won and got promotions, rewards, and more power. I got everything in these worlds by killing. So in these world we are killing for fun. The mechanics and systems behind these games are designed to encourage killing in certain areas and circumstances. So in these kind of games, I don’t remember how many lives taken away by me because I kill everyday and the lives are actually similar to my character.

Then I met sandbox games. In Skyrim, Fallout New Vegas and Watch Dog, mechanics and systems provide more variations on solving a problem. You can choose to kill since that is the most traditional way. But you have other options, such as bribe and persuasion. Compared to the games mentioned in the last paragraph, these games are less violent and more optional. Still, I don’t remember how many lives I killed too because killing is just one way to solve a problem (mostly a task) in the worlds. I am care about finishing a task instead of my way to finish it.

However, I killed an old man in This War of Mine. I killed him in a game one month ago but I still remember all the details of my behaviors and my mental process. And I still feel guilty. I Let me tell you that. My character was a cooker at that night, one of my companions was in charge of night watching at home and the other one was badly sicked in bed. I was going outside to scan for resources. I need food for my group and I need medicine to save my companion. Hospital was taken up by a group of soldiers so I had to test my lucks on an shabby building. It was said that there are foods and medicines but dangers as well so I took my pistol. Entering the building is pretty simple because it is a big building and few people lived here. I tried to be polite at beginning avoid entering the room which is taken up by others. I scanned for hours but failed to find anything useful. Even my character were murmuring that he is hungry. So I decided to take a risk. I entered a kitchen which is obviously belong to someone else. Then I got some food successfully and no one spotted me. Since I had stolen something, then I think I should steal more since there was already a penalty for stealing. So I walked around and entered a bedroom. All I spotted was the clear icon floating on the bed which showed that there was items inside. So I clicked that and my character found medicines! Oh, I can save my companions life! I took them. Suddenly, a dialogue popped out, “Don’t take the medicine. I need them”. Then I found that there is an old man lying on the bed. Obviously, he was ill. Actually, in the game, I always try to help others. I traded my medicine to one of the son whose father is ill to save his life. I went outside to help my neighbors. But now I was taking other’s medicines, I was taking his life supplements away. Without any hesitation, I pulled out my gun and shot at his three times before he died. I run away and back to home. Finally, my companion still died in sickness because it was too severe and I was killed when suffering a robbery later.

Why I kill that old man? I keep thinking about it. Rationally, killing a non-enemy using bullets is a waste of bullets and they are precious in the game. The instant thought is that I took his medicine so he would die. I was just try to make it easier. It was nice to him. But now I can admit that I killed him because I felt guilty to steal his medicine and his existence was evidence of my guilty. So I killed him for my own relief.

Emotions in game are precious and important. So one interesting question is why I feel guilty to that exact old man instead of the former bodies on my game experience path. I consider the followings might be part of the reasons.

First, in This War of Mine, there is no exact goal for players. Players struggle with survival everyday, but the game never says that is your goal. Without a goal, players cannot blame killing to game. They have to take their own responsibility for their own behaviors.

Second, when a character kill someone his mood and his companions’ and his moods will be low for several days. Exposed to others makes players more affected by social opinions.

Third, NPCs are responsive to the world. If the old man was just lying down or kept saying before I took medicine. I won’t feel he reacted to my behavior. Then I do not care about him any more.

Fourth, I died from robbery from someone else. I feel the hopelessness when suffering it.

In sum, This War of Mine provides a successful example of how to create a realistic and impressive world by an innovative way, evoking emotions.

almost monopoly.

In an economy where 3 players try to accumulate resources:

3 Corporations start with 5 kabillion doubloons + 3 kabillion units of unsold product in the pool (center of the table). One pebble is 1 kabillion doubloons.

Each turn players take a decision in Rock Paper Scissors style. Players can choose Action A (fist) to represent a selling an expensive designer product or Action B (open hand) to represent a cheap usable product .

There are 4 possible outcomes:

Outcome 1 – One corp. chooses Action A: this corp. takes 1 kabillion doubloons from each other player.

Outcome 2 – Two corps. choose Action A: these corps. both give 1 kabillion doubloons to the third player.

Outcome 3 – Three corps. choose Action A: all corps. put 1 kabillion doubloons in the pool. These represent all the unsold product because of saturation.

Outcome 4 – Three players choose Action B: the corp. with most resources proposes once, without discussion nor barter, how to divide the pool. If at least one corp. agrees the decision becomes effective. Otherwise, nobody takes anything.

The game ends when the first corp. is out of doubloons. The corp. with the most doubloons wins.

Alternate story: 3 hunter-gatherers cooperate and compete to get food to survive. Action A (fist) corresponds to collecting firewood, Action B (hand) to corresponds to hunting for meat. The resources held by players is their energy, resources in the pool are firewood.

Outcomes 1 and 2: If both meat and firewood is collected, the players can eat cooked meat, but the odd player out has the most leverage and gets to eat plenty, while the other players spent more energy than they can recoup.

Outcome 3: If everyone collects firewood, everyone loses energy. You can’t keep heavy firewood on you for the next day, so you just collect it in a common pool for later use.

Outcome 4: Everyone collects raw meat. There is an excess of meat, and the amount that can be cooked depends on the available firewood. The leading player proposes a split of the produced food, but without majority agreement the meat will go to waste.

The game ends when one player runs out of energy and dies. Of the remaining players, the one with more energy is stronger and rules the tribe.

In an economy where 3 artists try to make money off their art:

• 3 Players start with 5 money chunks + 3 money chunks in the economy (center of the table)

• Each turn, players can choose to produce and market Experimental (display a fist) or Commercial (display an open hand) art during their turn.

• Each turn, all players spend a money chunk on their art supplies (put 1 token in the center of the table).

• If one artist creates work in a different genre from the other two artists, they are able to sell it, because it’s a unique piece (gain 3 tokens from economy).

• If all artists make commercial art, the artist with the most money sways the economy and promotes whichever art they choose, proposing a way to divide up the economy’s available money, but can only do so with the approval of the community (at least one other player).

• If all artists make experimental art, everyone loses and no one is able to sell their art. No one makes any money this turn.

• When one artist runs out of money, they are disheartened and leave the industry, and the artist with the most money has less competition and is able to make money continuously. They win.

3 thieves rob a mansion and have made out with 5 worthless contraband items each. If caught, these items will surely be used as evidence to incarcerate said criminals.

Each turn thieves take a decision in Rock Paper Scissors style. Players can choose Action A (fist) or Action B (open hand).

There are 4 possible outcomes:

Action A = defensive action

Action B = offensive action

Outcome 1 – one player chooses Action A: this player takes 1 resource from each other player.

This means that one person defends themselves against two reverse pick-pocketers. The pickpockers overwhelm the one defender.

Outcome 2 – two players choose Action A: these players both give 1 resource to the third player.

The third player tries to reverse pickpocket two other players, third player is unable to accomplish either.

Outcome 3 – three players choose Action A: all players put 1 resource in the pool

Since players are not worried about reverse pickpocketers, they have time to incinerate their contraband.

Outcome 4 – three players choose Action B: the player with most resources proposes once, without discussion nor barter, how to divide the pool. If at least one player agrees the decision becomes effective. Otherwise, nobody takes anything.

All players work together to con some unsuspecting victim into taking a negotiable amount of contraband (as described above).

The game ends when the first player is out of resources. That player wins.

Egg Sperm Shoot!

By Elizabeth Agyemang, Madeline Finn, and Sandra Kang

In 2016, people became disinterested in sex. Thus, there is now a population problem:

3 Players start with 5 zygotes + 3 infertile eggs in the pool (it is where all the infertile eggs go).

Each turn players take a decision in Rock Paper Scissors style. Players can choose Action A (vagina) or Action B (penis).

There are 4 possible outcomes:

Outcome 1 – one player chooses Action A: this player takes 1 zygote from each other player.

Outcome 2 – two players choose Action A: these players both give 1 zygote to the third player.

Outcome 3 – three players choose Action A: all players put 1 zygote in the pool, where they become infertile eggs.

Outcome 4 – three players choose Action B: all players put 1 zygote in the pool, where they become infertile eggs.

The game ends when the one player is out of zygotes. The player with the most fertilized zygotes wins.

In the cutthroat industry of videogames, each player is a game studio with the capital to choose between developing risque-indie games (Action A) or mainstream triple A titles (Action B). However, gamers in addition to being dead, are a fickle, and competition is fierce. If the market is saturated with gray-brown first-person shooter with white men and brown hair, gamers will seek the refreshing color palettes of indie games. If the market is saturated with pigeon simulators, people will want to play a normal game. Thus, the studio that is making whatever the other studios are not making, will take capital from them. However, if all studios choose the triple-A path, there will be a boom in the industry, and the two studios can conspire as an oligopoly to divide up all the wealth. If all studios choose the indie path, everyone’s Kickstarter goes unfunded and all studios lose money, because indie games suck. If one studio goes under, they can only create indie games, and all the capital they receive goes to the bank to pay off their loans (removed from the game). When a single player survives with all the capital, they are declared the industry champion and inherit the title of EA. They can now shovel out whatever garbage they want, and gaming as an industry is ruined forever.

New rules, by John Choi, Christian Murphy, Dan Sakamoto, Kristina Wagner:

In an environment where 3 players try to cure their diseases:

3 Patients start with 5 diseases + 3 diseases in the pool (center of the table)

Each turn patients take a decision in Rock Paper Scissors style. Patients can choose Treatment (with possible side-effects) (fist) or Sneeze (open hand).

There are 4 possible outcomes:

Outcome 1 – one patient chooses Treatment: this player takes 1 disease from each other player.

Outcome 2 – two players choose Treatment: these players both give 1 disease to the third player.

Outcome 3 – three players choose Treatment: all players put 1 disease in the pool

Outcome 4 – three players choose Sneeze: the player with most diseases proposes once, without discussion nor barter, how to divide the pool. If at least one player agrees the decision becomes effective. Otherwise, nobody takes anything.

The game ends when the first player is out of diseases. This player is the winner.

Legend of Zelda games have long been associated with open worlds and exploration, but the main appeal to me has always been the sidequests. And when I think of sidequests in the Legend of Zelda series, one springs instantly to mind.

The Kafei and Anju sidequest is perhaps the most intricate and expansive quest in Zelda history. That alone is not what makes it stand out. The context of the quest is also remarkable. It is placed in a game that pressure you to keep moving through the placement of an artificial timer. With every action not advancing the plot or progressing through some sidequest, it seems difficult to justify some of the waiting that is required. Most noticeably, the quest REQUIRES the player to allow an old lady to be robbed in the first third of the game in order to progress in the quest, an action that is fairly out of character for our hero.

With the general attitude of this game as grim as it is (the various NPC’s all believe the world is about to be crushed by the moon, a fact verifiable by the increasing proximity of the moon to the town), the Kafei and Anju sidequest also stands out for its emotional quality. No matter how many times the player warps back through time, Anju will always be waiting for Kafei. Kafei’s curse and the subsequent theft of his mask leave him in disgrace, but he gives the player his pendant to give to Anju as a promise that Kafei will return. Once the player and Kafei discover the thief’s hideout, the two storm it and retrieve the mask, and only one hour before the moon comes crashing down on the town, Kafei finally meets Anju and they exchange masks in the formal wedding ceremony, creating the Couple’s Mask for the player.

The Couple’s Mask has fairly limited use in the game, and by the time players attain it, there is roughly one minute of real time before the game ends, and so generally players will have to reset the clock, effectively erasing all of the progress in reuniting Kafei and Anju. Nevertheless, the sidequest is a reminder of the power of love. Despite the misfortune surrounding the two of them, Kafei and Anju are the only two with a happy ending, and it is only with detailed work that the player can achieve this particular sequence. Amidst all of the death and destruction present in this game, the image of Kafei and Anju together, hand in hand, facing the end of the world with a smile and a promise to greet the morning together, is one that still echoes in my mind, years and hundreds of quests later.

Most importantly, the sidequest instills the game with meaning. With the player’s ability to reset the clock an unlimited number of times without restriction, it’s difficult to attach to many of the characters. After completing each of the four dungeons, players can just warp to the end and solve most of the problems in the game. But the Kafei and Anju sidequest has no shortcuts. Players must progress through the quest from the very start of the cycle to the very end. Nothing can be skipped, every action must be performed. And since the game is so short, the quest is easy to miss. Players that don’t see it assume that every NPC is like the ones they interact with – cowardly citizens that stay in the town at first out of the promise of money and then flee, leaving the soldiers to stay in town despite advocating for the evacuation of citizenry on the first night. But Kafei and Anju, knowing that the moon is bearing down on them and with no way to combat it, choose instead to wait for each other. They put their faith in you from the start of the game and, three days later, you are the only one left to witness their exchange of vows.

To me, this was the end. With just enough speed, I ran to the Clock Tower and finished the game. But the objective was no longer getting the mask back to the Salesman. Making sure Kafei and Anju got to see that morning was the true ending for me.

It’s not often that one sees a story told without words. Since the fall of silent films, dialogue has captured the basis of human storytelling. But in depicting non-human protagonists, few have tried and succeeded. Wall-E lasted 40 minutes (ignoring recorded human video) with only endearing robotic sounds. Other animated films feature animals, toys, or even automobiles that nonetheless speak the human tongue. So it is with a breath of fresh air that Machinarium enters: a puzzling point-and-click about a robot. Not only is the entire story told, but a vast metallic world is built, filled with other lively robots, all without a single word.

The secret: animation.

The game opens with our hero haphazardly cast out of the city, robotics parts scattered across a broken wasteland. After reassembling himself and maneuvering into the city, bits of story begin to reveal themselves. Occasionally, ideas are told through animated “thought bubbles”: black and white scenes or memories of the past. We see the two baddies bullying him, ruining his sandcastle, and finally stealing his girl and kicking him from the city. Despite the likeness to common tropes, there is something refreshing about guiding a robot through the hero’s journey back into a bizarre yet beautiful world. Every movement has character: the slightly clumsy but endearing struggle of the protagonist; the greedy shoveling of food into the fat nemesis’ belly; the lazy slump of the guard on duty. Coupled with the art and soundtrack, these tiny details build up a wonderfully crafted world of robots and metal parts, all without a single word of dialogue.

The first thing anyone with any knowledge of video games will notice about playing Number None, Inc’s Braid is that the mechanics of the game are a reference to Super Mario Brothers, from the simple fact of being a side-scrolling platformer, to the goomba-like enemies which one can only defeat by jumping on them. But the reference to Super Mario is not just a mechanical one; it turns out to be an important tool through which narrative meaning is conveyed. The first on-the-nose hint of this comes when player reaches the end of stage one and encounters the familiar scene: a friendly character emerges to deliver that classic bad news that the princess is in a different castle.

Cutting to the game’s end, it turns out that the player character is a scientist working on the Manhattan project, and the “princess” in the story is actually the player’s goal of completing the atomic bomb. This would be an impactful revelation on its own, but where things get really interesting is in the existence of an alternative ending. In the regular ending, you realize that due to your own warped perspective, the princess you thought you were rescuing has actually been running from your pursuit the entire time, revealing you to be the bad guy. But there’s a second ending, and because it is harder to reach, anyone used to the convention of alternate endings in games is likely to perceive this as the “true” or “best” ending. But in the alternative ending, the moment you reach the princess the bomb detonates. The good ending is also the bad ending.

This method of conveying a moral message by confronting the player with the idea that they were complicit in evil just by playing the game is not uncharted territory. It’s also a tricky device to really make work, since above any challenge to the player’s morality within the game is the fact that the developer built and marketed the game in the first place. What makes the alternate ending in Braid so meaningful however is the fact that the way to reach it—a perfectly timed jump onto a moving set piece—happens so quickly and without precedent that it almost feels like a mistake on the developer’s part. To be attempting this trick in the first place feels like trying to break the game, the aim of which—reaching a platform that seems like the game wasn’t designed for you to reach—is reminiscent of the same trick in Mario which leads to the warp zones.

What’s present in the nuance of this alternate ending is that first you must find out you’re the bad guy, and then you have to still be so determined to reach your original goal, so unfazed by the realization of the full implications of your mission that you’re willing to try to break the game to reach it. By referencing Mario, which itself references a common trope of rescuing a princes, Braid creates an occasion to reflect on a multitude of games the player has played in the past and consider a deeper reality for the characters than what was originally perceived, or even beyond what the developer may have intended. Braid opens the question: what exactly was Mario’s relation to Princess Peach, or Link’s relation to Princess Zelda beneath the surface of what the developers presented?

A while ago I played Limbo on my iPhone. I played it with a friend over the course of several weeks. The most thought provoking part for me was the elongated death scenes. I was often so eager to move on after a failure (and there were many failures) that I got impatient with the animation. Every time I died, I had to watch my character be impaled, or sink, or drown… The animations were intricate and individualized and beautiful. Clearly a lot of attention was paid to the death scenes and they were important (in a morbid way). After a few occurrences my own irritation became obvious to me and the lightness with which we take death and failure in video games. With a single minded commitment to completing the puzzle, and given the opportunity to immediately restart and often not deal with the consequences of failure… games that force the viewer to experience death in a slow and (slightly inconvenient way) really interrupt the gameplay and for me make me think of the incongruousness in experiencing failure in games.

A while ago I played Limbo on my iPhone. I played it with a friend over the course of several weeks. The most thought provoking part for me was the elongated death scenes. I was often so eager to move on after a failure (and there were many failures) that I got impatient with the animation. Every time I died, I had to watch my character be impaled, or sink, or drown… The animations were intricate and individualized and beautiful. Clearly a lot of attention was paid to the death scenes and they were important (in a morbid way). After a few occurrences my own irritation became obvious to me and the lightness with which we take death and failure in video games. With a single minded commitment to completing the puzzle, and given the opportunity to immediately restart and often not deal with the consequences of failure… games that force the viewer to experience death in a slow and (slightly inconvenient way) really interrupt the gameplay and for me make me think of the incongruousness in experiencing failure in games.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wuu1OntyQ54

The video contains the section I’m talking about. Ignore the commentary.

The Vanishing of Ethan Carter is an environmental narrative experience centering around the player character’s search for the boy who summoned him to the town the game is set in. With intense and mesmerizing graphic detail, the game world uses sound and context to lead the player from narrative event to narrative event in a patchwork collage of nonlinear, non-apparent character development. The game begins with the words: “This game is a narrative experience that does not hold your hand.” This fourth wall breaking introduction is an atmospheric undercut, but forgivable since it precedes all other events in the game. However, this sentence is an accurate description of the game’s difficulty and how it uses difficulty as a medium to tell subtle elements of the story. For example, there is no conventional death in the game, just simply noticing and failure to. Sections of the game function on separate mechanics, and figuring out these loosely defined puzzles also provides a layer of agency. In these sections the player “solves anomalies.” These anomalies are faintly noticeable traces of the extraordinary, events you may fail to notice as you progress, and provide a significant chunk of the game’s more nuanced character development. The series of actions to progress in these areas are all different, yet they share the same feel with only one exception. The scene called The Curse of the Sea-Thing destroys all of the subtlety and meticulous layering of environment and narrative with the most seductive of mechanics: the jump scare. Of all the anomaly solving scenes in the game, this one is by far the most cheap and the most scary. The player approaches the location of the scene by descending a long, barely lit tunnel in the earth, spiraling down for several minutes. At the end of the tunnel the player is confronted with a written warning: Turn back, the ritual failed. Candles freckle the tunnel before the player and water pools at his feet. The music changes into something yet to be heard. In sync these elements form a cohesive, anxious precipice; all done with atmospheric and environmental cues. Yet, if the player marches forward, ignoring the warning, his character is met with a single rasping wail and a slenderman archetype at his soggy heels. At first play through, the player may continue ahead at a self controlled pace, and is caught off guard by this figure who rudely disrupts the ambiance of the world. On subsequent playthroughs this figure becomes an active excuse to ignore all environmental elements and tear through the tunnels with abandon. This is a major break in the flow of play and is not effective in a game that is, on all other accounts, an environmental narrative. For a game that claims to not hold your hand, this section relies heavily on pre-existing, easy-to-scare horror tropes that here fall flat. From a design perspective, this break in flow, which is never repeated, is an annoying blister, since it is required to finish the game. From an artistic perspective, this section is a fault in the metaphors of death (from the perspective of the dying) that this game addresses. Yes, this portion forces the player to feel fear, and death can involve a great amount of fear. Yet that fear is short lived, anticipated, and entertaining (that’s why that trope/mechanic has been so commercially successful.) Death, especially the sort of deaths that the game talks about, is not short-lived. It is permanent. And certainly dying is not entertaining. Terminal events are not fondly reminisced about by the deceased.

Gone Home

It is a first person adventure game. You are placed in the shoes of Kaitlin. She is returning home after some time abroad to find her house empty. You are fed clues throughout the game, though are not given any direct instructions or possible game outcomes. As you move through the house, you are able to turn on lights, pick up objects, move through rooms, and find clues. The game becomes interactive by players’ ability to move through the house and engage with objects that are found. As you move around the house, periodic audio journal entries are revealed.

It seems as though the environment we are placed in and the actual narrative of the story do not match up appropriately. Lonnie and Sam are two characters who fall in love and run away together and that is revealed at the end of the game. While you play the game, however, it is grim and eerie in the lighting, aesthetic, and pouring rain audio taking place within the home. You have the sense that something terrible has taken place. The build up surrounding the game seems heightened beyond the actual conclusion of the game. There is a development and tension that does not reach a corresponding fruition.

Game Critique of 2048

I have very little experience with playing games. The assigned Home Play/Twine games from this course make up a considerable portion of my overall game knowledge. Over the summer, however, I found myself completely addicted to the game 2048. What I found to be so addictive within the game is the idea that the challenge is attainable. The objective of this puzzle game is to combine the tiled numbers until you reach the number 2048. Players swipe the tiles back and forth to add them together on a 4×4 grid board. The game’s layout and object are easily grasped. Though the intent is simple, it does involve strategy adjustments. I experienced a rush of excitement when I moved forward in the game. The numbers double and the color configuration is adjusted. The visual feedback of advancing within the game contribute to its addictive nature.

For over a month during high school, I played a game called Receiver for at least an hour every day. Initially this was because I was hell-bent on beating it, but as I tried to finish this short little game over and over it became an abnegative, almost meditative experience. Receiver is a first-person shooter made by Wolfire Games, originally developed as part of the 7 Day FPS Challenge. At its core, it’s a game where the player moves through a semi-randomly generated world, fighting robots and collecting a set of 11 tapes. This concept is expanded into a game which, for the right player, uses its mechanical difficulty to highlight its themes and create extremely engaging gameplay.

Receiver’s main claim to fame is its gun mechanics, which are some of the closest to operating an actual gun you can find in video games: every action you can perform with a handgun has a key bound to that action in-game. For example, if you’re using the basic handgun and want to reload, you have to remove the clip from the handgun, put the gun in its holster, insert bullets one by one into the clip, pull your gun back out of its holster, put the clip back into the gun, and cock said gun. The closest thing you get to a tutorial is being able to open a list of all the key commands for your gun, and the devs decided to give you a convenient ‘drop whatever you’re holding’ button that has no purpose in-game beyond letting the player accidentally drop their gun while attempting to use it.

On top of that, Reciever’s world operates on a relatively simple, but extremely harsh, ruleset. taking a single bullet kills you. Getting hit by one of the small flying, electrified drones kills you, falling off of the endless skyscraper you’re exploring kills you. Falling relatively short distances kills you: Indeed attempting to travel down a flight of steps at a full sprint is liable to kill you.

The interesting thing about having a game that’s so difficult to actually operate is that is requires an extremely high level of focus for the player to learn and play the game. By necessity it requires extremely deep immersion. The kind of immersion that, once you get good at playing, has you trying to dodge a slew of bullets by near-leaping sideways out of your chair when you mess up.

However, it is not the game’s mechanical difficulty alone that makes it special. It is that fact that it’s difficulty is almost exclusively mechanical difficulty. If it were simpler to play, you would likely see every environment that it has to offer in under an hour, and anyone remotely versed in FPS and stealth gameplay would see nothing new. To put it simply the game is highly repetitive.

This combination of challenge is, for a normal gaming audience, terrible. But Receiver isn’t so much a game as it is a sort of skill. This is why I am willing to call the game meditative. Zen buddhism explores the concept of unconscious mastery of a skill as a form of meditation: That being able to do something extremely complex tasks without thinking allows the actor to enter a special mental space. The historical example for this idea is archery, but the exact same idea of unconscious mastery through repetition is ever-present in, and fundamental to, Receiver.

I never actually beat Receiver, and I have only found one documented case of it being beaten . This game, that I devoted days to can be beaten in 25 minutes. Frankly, I would have been unsurprised to learn that it was in fact unbeatable. The game’s story is based on the concept that you are trapped in some form of lower reality, and collecting the tapes (messages from higher beings) will somehow set you free. A simple enough narrative that has a strong links with both buddhist philosophy and the game’s mechanics. Receiver is very cyclical. the second you fail you start anew, with a similar but different map, possibly a different gun, but the same goal and exact same behaviours. And it is because so little changes when you play it that this Zen state is explorable in Receiver.

The goal of this game is not to be noticed. You will have to combat language barriers, local customs, and more to avoid attention and attempt to find a job. Good luck!

Play the downloadable version!

***!!!UPDATED!!!***

a short story about a loved one, in train format

structure below the cut

Download to play: https://www.dropbox.com/s/kemvhtdbtllx38s/BABY.html?dl=0

You hear the sound of a gunshot. What do you do?

andrew.cmu.edu/~mkellogg/ExpGameDesign/Gunshot.html

EDIT 9/23/2015

I updated the game to remove the run away and ignore options as suggested. I changed the link colors in order to create more contrast with the background when there are 3 options.

Emergence is a game about an artificial intelligence trying to solve the meaning of life.

Journey through the snow and be reborn.

Please download the game to play.

Click here: Red Rising

*Updates:

-text

-format

http://www.dansakamoto.com/egd/twine/

A semi-guided meditation on trauma and perspective, adapted from a poem by Daniel Darwin. Includes sound.

Play as a newly hired and aspiring janitor! Create your own filthy way out of this messy rat race! Pursue your ambitions or revile in your disgusting self-failures!

EDIT: UPDATED AGAIN~

A Twine story written By Bryce summers.